Note: this article was published before the author came out as trans and non-binary, and originally referred to them by their birth name and pronouns.

Ten years after its publication, Jul Maroh’s “Blue is the Warmest Color” (“Le bleu est une couleur chaude,” lit. “Blue is a warm color”) remains a poignant and moving love story that’s been overshadowed by a controversial film adaptation. Be aware that there will be spoilers, even if you have seen the film version.

Written with art by Jul MarohEnglish edition

Translation by Ivanka HahnenbergerClementine is a junior in high school who seems average enough: she has friends, family, and the romantic attention of the boys in her school. When her openly gay best friend takes her out on the town, she wanders into a lesbian bar where she encounters Emma: a punkish, confident girl with blue hair. Their attraction is instant and electric, and Clementine find herself in a relationship that will test her friends, parents, and her own ideas about herself and her identity.

Vividly illustrated and beautifully told, ‘Blue is the Warmest Color’ is a brilliant, bittersweet, full-color graphic novel about the elusive, reckless magic of love. It is a lesbian love story that crackles with the energy of youth, rebellion, and desire.

Despite the synopsis, “Blue is the Warmest Color” is very much a story about loss, life, and regret. It begins when “Clem” has died, and Emma visits her childhood home to collect her diary. It’s blue, which Clem says in her letter to Emma “has become the warmest color.” Likewise, it’s not quite accurate to say the book is in full-color: the lion’s share of the book is a flashback rendered in black-and-white.

Let’s get my sole criticism of the book out of the way: it is really hard to read Clem’s narration at first, being written in that distinctive French cursive, and then squeezed into tiny caption boxes. You begin to worry, “am I actually going to be able to read this?” Fortunately the dialogue is in block letters like a typical comic, and when Clem’s diary entries resurface, you feel more comfortable slowing down to concentrate on reading them.

Clem’s diary transports us to 1994, when she was 15 years old, the legal age of consent in France, and so the story begins exploring her burgeoning sexuality, leading to failed relationships with boys and girls. Her mind is preoccupied by one girl – a tall beautiful girl she walked past on the street, a girl with blue eyes and blue hair.

It’s a stroke of genius that blue is the only color visible in the majority of the book: it symbolizes how Emma is the sole glimmer of hope in Clem’s life, brightening her dull and melancholy life. When Clem fantasizes about Emma for the first time, Emma’s skin glows white, like an angel or fairy, while the blue dye drips down her arms onto Clem’s body, giving her her vitality.

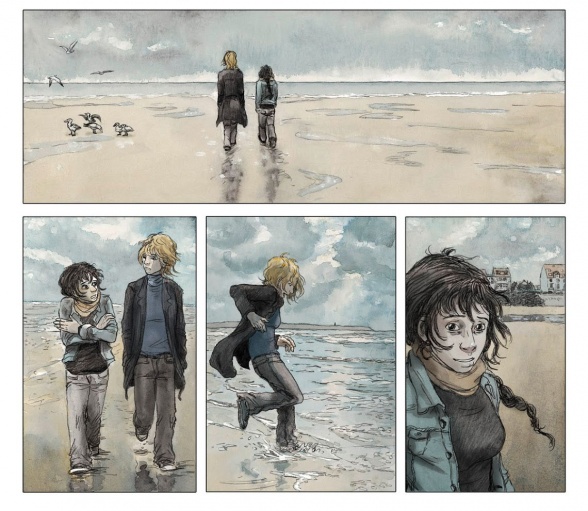

But that doesn’t mean the rest of Maroh’s artwork is dull: it’s incredibly striking, like we’ve stepped into a world of memories sketched on paper, raw, immediate, and intimate – you can almost smell the freshly smudged pencils. That part is probably my imagination as well though: it’s not often you read a comic and genuinely wonder how it was made. It’s fantastic to reread and realize which panels are using black and gray watercolors, and which ones simply have well-blended shading; likewise I keep looking at the art to see any signs of pens in the black-and-white sections, because it looks so earthy.

One of the most pleasant surprises about the book is that it’s not a “realistic” graphic novel: Maroh’s character designs are clearly influenced by Disney and manga, with huge eyes and small mouths. It helps endear us to the characters, ensuring Clem’s hormonal frustrations don’t become tiring, with beautifully expressive moments, like when she gives a dorky mile-wide smile on realizing she’s in love, or the sheer astonishment on her friend Valentin’s face when she confides in him that she and Emma have had sex.

Continued belowAh, the sex: it’s graphic and arresting, but only a microcosm of Maroh’s whole achievement. They started drawing and painting this when they were 19, finishing it five years later, and it really feels like it: you’re visibly aware of their evolution as an artist, becoming — like Clem — more confident, increasing the size of the panels; devising more abstract imagery; drawing more ambitious backgrounds and landscapes, as well as (yes) sex and nudity; and finally transitioning closer to the present in 2008 with fully colored pages. You can see as the book progresses that they drop simpler narrative devices like thought bubbles in favor of letting the reader imagine what Emma is thinking: appropriately, the final page of the book is that most silent of mediums – an entire painting.

As a story composed over five years, with events spanning over a similarly not inconsiderable number of years, “Blue is the Warmest Color” certainly feels like a lengthy read, and some may find its steady pace meandering. Likewise, some readers may feel irritated such a celebrated LGBT graphic novel is about the death of an LGBT person, given how sadly common the idea is, but this is a story from Maroh’s heart, and it would be churlish to dismiss their work because others haven’t always explored that theme when appropriate.

I think anyone — whether they’re LGBT or not — can appreciate Maroh’s visible labor of love, and deeply relate to their tale of longing for affection and acceptance: everyone’s felt like an outcast at some point, and the theme of homophobia — casual, internalized or otherwise — is an important reminder that even places like France, the land of “liberté, égalité, [and] fraternité,” were not free from such pain a fairly short time ago. When you reach the end, you’ll imagine you have lived a lifetime with Clem and Emma, and perhaps you’ll feel the devotion they had for one another too.

By the way, if you were hoping for comments about how the film compares to the book, well, you’re out of luck: I haven’t seen it. Maroh’s criticism of the film, and lead actresses Léa Seydoux and Adèle Exarchopoulos’s complaints about director Abdellatif Kechiche, are partly why I chose to read the book instead. (I might’ve watched it if it hadn’t left Netflix UK.)

I am, however, a big fan of the video game Life is Strange, a homage to the comic: the protagonists, Max and Chloe, were dead ringers (no pun intended) for Clem and Emma, and depending on which ending you choose, the game similarly becomes a rumination on love and loss. Point is, whether you’re a fan of the film or the game, or neither of those things, you should definitely read “Blue is the Warmest Color” — it truly remains the warmest ray of light in comics.