Creating truly effective horror in comics is notoriously difficult. In no other medium does the audience so thoroughly control the pacing of the narrative, and with the silent nature of comics making things like jump scares tricky, tension-building takes a skillful combination of script and art. Luckily, “Locke & Key” has that skilled pairing thanks to Hill, Rodriguez, Fotos, and Robbins.

‘Welcome to Lovecraft,’ the first volume of the six-volumes that make up the main series, is also indicative of the whole run, in that it’s about so much more than horror. It uses supernatural horror, in fact, as a touchstone: a narrative backbone with all of the tropes and expectations fully loaded and ready to subvert. At its heart is a meticulously crafted series of events that unravel a greater mystery, one with a broken family at its core, each member of which is searching for answers. Welcome to Lovecraft. Welcome to “Locke & Key.”

Written by Joe Hill

Illustrated by Gabriel Rodriguez

Colored by Jay Fotos

Lettered by Robbie RobbinsFollowing their father’s gruesome murder in a violent home invasion, the Locke children return to his childhood home of Keyhouse in secluded Lovecraft, Massachusetts. Their mother, Nina, is too trapped in her grief—and a wine bottle—to notice that all in Keyhouse is not what it seems: too many locked doors, too many unanswered questions. Older kids Tyler and Kinsey aren’t much better. But not youngest son Bode, who quickly finds a new friend living in an empty well and a new toy, a key, that offers hours of spirited entertainment. But again, all at Keyhouse is not what it seems, and not all doors are meant to be opened. Soon, horrors old and new, real and imagined, will come ravening after the Lockes and the secrets their family holds.

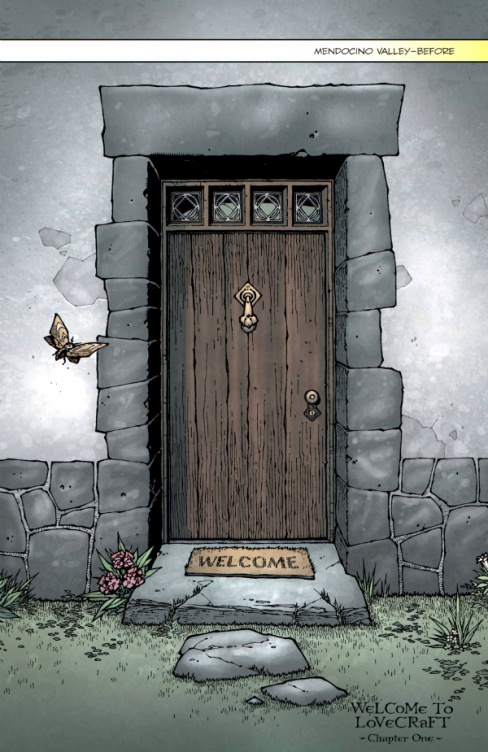

It all starts with a door. A full-bleed splash page showing us the doorway to an unknown home. The welcome mat is out, there are pretty flowers surrounding the front step, and a butterfly floats by; this is very literally a welcoming invitation into the book itself, a door just waiting to be knocked on, to be opened, for the adventure to begin. Look closely at that image though, and you’ll see that the butterfly is more like a moth, and the intricate pattern on its back looks a lot like a skull. The doorway itself is inviting, but there may be a reason why the door is closed. There’s an edge to the world outside, a hidden darkness just hovering in the peripheries of your vision.

With a title like “Locke & Key,” it makes sense that doorways would be a narrative through-line in the book. They take on a very literal significance when the supernatural elements of Key House come into play, but from that very first page they’re always present in the art, in ways that frame the characters, or frame our view of certain scenes. Doors become portals to other worlds and fantastical possibilities in this series, but more than that, doorways are a means of access, of exploration, of discovery; a closed-door representing the denial of those things. They signify the transition from one place to another, of which there is a great deal of in this story, but they can also signify an escape, either to somewhere or from somewhere else.

“Locke & Key” follows the Locke family, specifically the mother Nina Locke and her three children: Tyler, the eldest son; Kinsey, the daughter; and Bode, the youngest son. The seemingly random yet brutal murder of their father (through a home invasion, no less. Characters ignoring the unspoken rules that govern the doorway to a home, invading that privacy we all take for granted and abusing those within) proves to be the start of their journey, emotionally but also physically. Upon strict instructions from the now-deceased father Rendell Locke upon his death, the family moves across the country to Lovecraft, Massachusetts, and into Key House: a looming family home that’s overseen by Rendell’s younger brother Duncan. From there we begin another journey, one of discovery. This house is more than it seems, and when Bode finds a secret key with supernatural properties, we learn that everything that has happened, and everything that continues to happen to the Locke family is connected, and it all comes back to this set of mysterious keys.

Continued belowThe structure of these early chapters is deliberately non-sequitur, choosing to cut to the consequences of previous scenes before going into the specific details. Like peering through a half-open door, we’re only allowed to see a small piece of the puzzle. It’s this conscious eye on pacing that allows the tension to build, and while the scenes of violence are graphic and bloody, the real horror is the seeping feeling of dread that pervades the story. The initial scene of carnage where Rendell Locke is murdered is left mostly implied at first, transitioning from him opening the door on his imminent murderers to his son Tyler – our focal point for the first chapter – at the funeral. This drastic cut lets us know that yes, while there’s more to these events yet to be revealed, the point of the narrative is Tyler and how it’s affecting him. We don’t even get to see whether the mother survived the assault until a full twelve pages later, with only our assumptions to comfort us (it wasn’t a double funeral, after all).

By restricting the specific details of such crucial, life-altering events, Hill is able to effectively control how we read the story, and even control our focus moving forward. If the events unfolded linearly then the contrast between past and present wouldn’t be so jarring, our emotions so turbulent, and the scenario so unpredictable. This first chapter is a tight character study on Tyler – you can tell by the way we often see through his eyes in Rodriguez’s art, seeing things that are only happening in Tyler’s head, watching his memories from his point of view. His life, his view on life, is understandably chaotic, so by mixing past and present in this way, Hill and Rodriguez are throwing us into that chaos too.

Later chapters in this volume look at events from Bode’s point of view (chapter 2), Kinsey’s point of view (chapter 3), and even Rendell’s killer’s point of view (chapter 4), before opening up to a more free-flowing narrative in the final two chapters, giving us a real sense that events are unfolding frenetically and unpredictably as we close out the volume. While there’s a very explicit narrative reason why the Locke children are important characters to follow, that reveal is in a later book. For now, it’s enough of a reason just to get inside their heads and get to know these kids as they recover from the most traumatic event of their lives. The emotions they display immediately following this tragedy will inform their decisions moving forward through subsequent volumes, so having the chance to fully explore those feelings is vital here.

A theme that shows consistently through the artwork is that of small changes. One of the ways in which Rodriguez controls the pace of our reading, as well as play with the structure on the page, is by using the same panel backgrounds over and over again – fixing our viewpoint unflinchingly as we see events and people move around the space. This, again, feels like we’re stood in a doorway looking in; it feels like a theatrical decision, where we are literally the fourth wall on occasion. An early scene shows Tyler sat in the hallway of his home, as his father’s wake happens in the next room. Tyler is sat on a bench on the left, and we see characters walk the expanse of hallway across to him to interact. For twelve panels, we do not move from that viewpoint, with only incremental changes to the background letting us know that time is passing. It’s no coincidence that there is a door either side of the scene too: one into the wake and all of the guests, the other to his parent’s bedroom and the bright red urn holding his father’s ashes.

Often Rodriguez will employ this technique of the unwavering ‘camera,’ and its usage signifies a slower, more deliberate pace to those scenes. Three panels can move the story along significantly, but with this technique, there are times when a whole page is just a few seconds. There are also times when the changes between those panels are made more significant by the contrast with what’s the same: a crying Kinsey on her bed is framed in the same way as the following panel – a flashback to her hiding from her father’s killers; simple panel mirroring allows us to see that she may be safe on her bed, but her mind is still trapped within those terrible events.

Continued below

The introduction of a well within the grounds of Key House presents a further exploration of a portal which, much like the doorways that pervade almost every scene, symbolizes a gateway to the unknown. Rodriguez will frequently open up the panels to a full page spread, and on no less than eight separate occasions do doorways or portals play a significant role in the framing of that image. Opening up the panels in this way does literally open up the imagery; expanding the action to a whole page signifies the importance of what’s happening and freezes that moment in time for you to absorb without the distraction of other panels. On one occasion, the page turn transitions from one full-bleed showing one side of a door, to another full-bleed showing us what’s happening on the other side of that same door. This allows the physical act of reading the book to become synonymous with navigating the passageways of this house: while the characters are restricted by the locked door, we the readers are allowed to ‘open’ that door by simply turning the page.

‘Welcome to Lovecraft’ is clearly the opening volume of a consciously crafted and meticulously detailed supernatural horror. There are seeds planted in both the art and the script that won’t pay off until volume six, and by then you’ll want to go back and re-read the whole thing with fresh eyes. There’s a real sense that you’re in good hands with both Hill and Rodriguez – both come from excellent backgrounds in the genre, after all. It’s revealed in the back matter to later volumes that Rodriguez created an accurate blueprint of Key House so that all of the character movements would be accurate and consistent throughout the series. That’s not only an example of the level of detailed craftsmanship that is echoed in every part of this book, but one also wonders if there are times when he deviated from those blueprints in order to give the readers a subconscious sense of unease or disorientation, much like visionary director Stanley Kubrick did on the set of The Shining.

“Locke & Key” is a wonderful exploration of grief, legacy, and responsibility, as well as examining what it means to have a childhood taken away from you at such a young age. This opening volume, ‘Welcome to Lovecraft,’ is an open door waiting to be walked through, an adventure waiting to embark upon, a darkened room waiting to be explored by someone brave enough to cross the threshold. It shows us fantastical things happening to characters through their use of magical keys but contrasts that with the very real, grounded, graphic violence that one human commits against another. Once you’ve been welcomed in, there’s no way you’ll want to leave until you’ve finished the whole series, but this opening volume has a satisfying structure that provides closure to a series of events while leaving the door open to the mystery still unfolding.