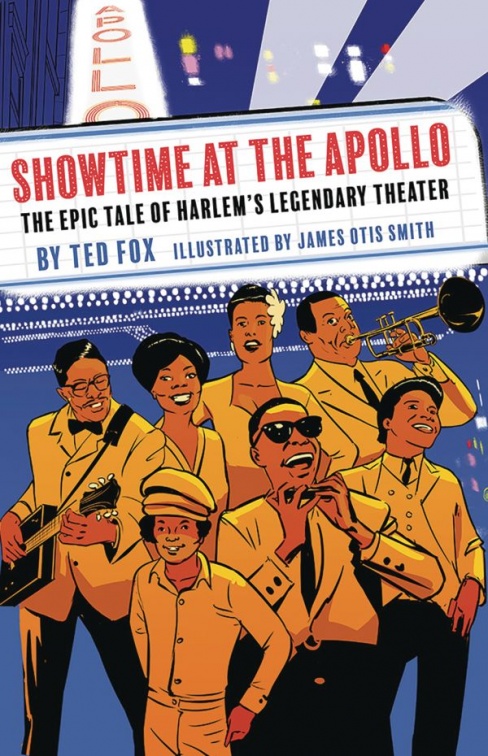

Early next year, Abrams will release “Showtime at the Apollo: The Epic Tale of Harlem’s Legendary Theater” by Ted Fox and James Otis Smith. Fox had written a history of the Apollo over 35 years ago, which is considered by many the definitive history of the theater. Now, he has collaborated with Smith to tell the story in a graphic novel, which traces the theater’s history from its start to the modern day. We spoke with Fox and Smith at New York Comic Con 2018 about the project, making comics out of music, and what Apollo show they wish they could have seen.

I grew up in New Jersey. I grew up watching Saturday Night Live. In this area, after Saturday Night Live, then Showtime at the Apollo begins. That was my first introduction to the Apollo Theater and anything involved in the Apollo Theater. As I got older and I became a musician myself and a fan of music, the Apollo Theater has this incredible history and import. Not just through music, but for civil rights and for New York in general, the Apollo was really an important location. What drew you to tell this story?

Ted Fox: Well it’s interesting speaking specifically about the graphic novel, I realized most people today like you, know the Apollo from Showtime at the Apollo. The book actually starts out cold with the Apollo as people know it today: from the tv show, they know Obama was up there singing Al Green, they know Paul MCartney played there, Bruce Spingsteen and Jay-Z and all these famous people. That’s the Apollo today: a mythical place with this great aura. But how did it get that way? Why this little theater on the 125th Street? What’s so special about the Apollo? So that’s how the graphic novel starts off.

When I wrote the original book in 1980 when people didn’t really care about the Apollo, didn’t really know about it when it was essentially closed and people thought it was dead and Harlem was on its ass and the city was in the worst shape it had ever been and nobody really cared. So, the idea was to contrast how people know about it today to what it was like back then. And then how this re-birth happened and also how the whole theater started.

The story of the Apollo is basically the story of American popular culture in a nutshell. You can trace all of the streams of the music, the dance, the comedy that we love today, back to this little theater on 125th street.

I find that to be a fascinating story because like you said, it does mirror the New York story so much. Way back before that even, you know 125th Street was white before the Apollo opened in 1934. So the Apollo when through the whole, you know, demographic changes of Manhattan, of New York City. And that’s also we’ve talked about that in the book and James illustrates it in the book, how you know, Harlem actually started further uptown and only gradually moved out to 125th Street so forth. So you’e right, the Apollo story is very much the story of New York as well.

And I think that as time has gone on, New York has gone from an area where people were terrified to go, it was spoken about in hushed tones to a place where it’s a destination and the Apollo again is a destination. James, It’s hard to look back with eyes that don’t see what you’re seeing now. How did you approach it going back to all the different reincarnations of the Apollo? Did you use a lot of reference? Were you trying to be as realistic as possible or was it about capturing the tone of the Apollo in these different eras?

James Otis Smith: Well, I really wanted to get the layout of the Apollo right. Because I dreamed of someone who performed at the Apollo, reading the book and then going, “That’s not where the dressing room was.” So I wanted the dressing room to be where it was even though to the reader, I mean just like a couple of lines that make up a wall or whatever, you know. The general reference thing, what’s cool about that is that if you take — if you have a street that you know and you get a picture of that street from a hundred years ago, I mean it’s not the same thing.

Continued belowSo, just making it look like the photograph wasn’t — or basing it on the photograph – wasn’t enough to make it different and enough to make it interesting to me because I have a short attention span, I get bored. So the fact that like, “Oh, this is not what a 125th looks like now,” that makes it interesting for me to try to draw it.

So many times artists are trying to tell a true story, get hung up on making everything look perfect especially people’s likenesses. Trying to get a likeness to be this absolute portrait image and it loses some of its soul, loses some of its movement, some of its looseness. And I felt that the book never relied too much on trying to make anyone too perfect. Instead, the essence of each person really popped up the page for me. I really appreciate that.

JOS: First of all, thank you so much. Secondly, that actually was surprising amount of work because there were times where I would download a photo of someone and I would draw them and then I would look at it and go, “Well that looks like a photograph.” And then I would re-draw it based on my drawing of the photograph. So some of those drawings there are like 2 or 3 times where it’s like my drawing and not like tracing up a photograph.

Telling a story in a prose book allows you to go into more detail, which works better than trying to cramp every detail into a panel. So how did you distill your book into something that felt lively as a piece of sequential art?

TF: Well, distilling is actually a really good term for what adapting the book was because the original book is the definitive history, its complicated, there’s a lot history, there’s a lot of social criticism, there’s a lot of different screens that are coming in there, and that’s what you need in a book like that to be.

For a book like this, and James and I talked about this from the start, we really wanted it to be a narrative, a story from. It has a beginning, middle, and an end; a three act kind of arc. And as I look at my [original] book, I was able to tighten it up, which was a tremendous amount of fun. I know the story inside and out having lived with it for 40 years now. So it was a challenge and also a tremendous amount of fun to get it down to an actual, flowing narrative that works all the way through and if we succeeded, that’s when it should be. That’s certainly what, you know, what I tried to do, what both of us tried to do.

And that’s a tough balance for both of you to strike, because you don’t want to short-change the history, because this history is important, but it is similar to the photo reference. You don’t want to shortchange what the place really was like; what the people really were like. Ultimately, your job is story-telling. Your job is to give the reader something to hold on to and do enjoy then maybe dig deeper afterwards.

TF: And you have to contextualize it. So, it’s not just the story of you know, how swing music morphed into, you know, into jazz, into bebop, morphed into rhythm and blues. They are all of these social situations that are going on that affected all of this. You know, the World War II, The Great Depression, the Civil Rights Movement. All of the different things that were going on. You have to be able to bring that in too because this story is part of all of that. It’s driven by that and it also pushed some of those social situations forward by what was happening in the Apollo itself.

Obviously you have to cut some stuff from your book and there are stories you couldn’t tell in the book. What’s the story you guys wished you could have told in the book? What do you wish you could add?

TF: That’s a good question. That’s a good question. You know, I’m going to have to come up with a good answer to that because that’s really a good question. I think I got all of the essential things in there. There’s nothing I walked away and said, “Boy, we really should have told that,” because I think we did tell all the essentials. I think, you know, it was more a matter of realizing, prioritizing, understanding what were the keys to the stories. It wasn’t always the stories of the most famous people, you know. It could be the story of Sandman Simms,, this great dancer who was also, you know, an executioner on Amateur Night.

Continued belowHopefully I got everything in there but that’s a good question. I’m going to have to go back and read my original book. What else could I put in there?

It’s a good thing to leave your audience wanting more. That’s better than having 50 pages left and you think, “oh God, I wish I just got to the point a little bit faster.”

TF: There are more characters, you know, in any different era that I talked about that you know, weren’t necessary to talk about to advance the narrative. But they’re interesting in their own way.

So much of that book was about music and music is a notoriously tough thing to illustrate, and yet, you managed to have rhythm and movement in your work. How do you do that? How do you get that from something you hear in your ear to see with your eye?

JOS: Most people like to compare comics with movies for thee obvious reasons. But actually the metaphor that always made most sense to me is music.

Oh really?

JOS: Yeah. And I do think of comics the way I think of music. And so I guess it’s in a way, it’s hard for me to answer that question because it’s kind of like well it’s just like when you play a guitar, right? But yeah, I do think a lot about like, okay, I’ve done a lot of these kind of angles or I’ve done this with the page, now I need to balance that by doing the opposite. That kind of thing, you know. I don’t know if that gives you the answer, but…

Absolutely it does, yeah. Last question for both of you. If you can go back in time, see any performance of the Apollo, from the beginning to now, what would you want to be there for?

TF: Obviously James Brown. The ’62 show—

That’s what I would say, too.

TF: Absolutely that. The other one would be Lionel Hampton, which James so beautifully depicted. You know, he marched off the stage with the band. That would have been a thrill. Most of the gospel shows.

JOS: He did say one.

TF: So you get your money back.

JOS: Probably Funkadelic.

That would have been good too.

JOS: That Funkadelic show would have been incredible.

TF: I saw that show.

Did you really? At the Apollo?

TF: Yeah. If you look at that, at the end of the book which is the part of the Funkadelic finale, there’s actually a little picture of me in the audience.

I can’t imagine Funkadelic on that stage. I’ve been in the Apollo a few times and it’s a smaller stage than people realize.

JOS: Working on this book was the first time I was there. And I was like, oh my God. It’s like a closet, you know.

Right.

TF: And the dressing rooms. The whole backstage scene is so small.

It’s not set up for a modern audience. We’re all too fat for the seats now. And the balcony incline going down…

JOS: Oh my God. It’s terrifying.