I want to say something that I know will sound cliché, so I’ll get it out of the way now: for having just three letters, ‘art’ is a pretty huge word. Art has been a part of human lives since before most anything else. It’s been a part of who we are longer than written words and non-naturally occurring shelter and because of that, it dictates so much of our world. Even the most generic laptop or boring looking office building are, in their own ways, objects of art. Someone had to imagine what these things would look like and commit those ideas to paper. Now, once those ideas are presented to the world, they’re open to criticism. I said that the hypothetical office building was boring, which is an indictment of its design. If I, or whoever was commenting on the building, had a little bit of practical knowledge about art and design, then you could probably have a discussion about why the building looks boring. This thinking can be applied to any type of art, but we’re all here to read about comic books, so that is where our focus will rest. Mostly.

The idea of comic art is one that’s frequently discussed, but just as frequently is it discussed, it’s misunderstood. How many times have you been in your local comic book shop and heard one of the staff members or customers loudly disparage a certain artist? It doesn’t matter if it’s Frank Quitely or some avant-garde cartoonist, every artist has their critics, and quite often, what they’re being lambasted for is much more a stylistic preference than a significant issue with the art. The question is, how can you – meaning everyone, from comic reviewers to Joe Q. Comic Reader – better understand comic art so either a) your discussions and complaints have more merit or b) you can appreciate the work of artists (even ones you don’t like, stylistically) more? That’s where I come in.

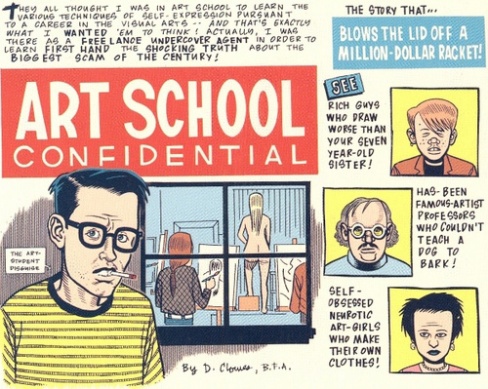

I know that it takes a certain type of asshole to blow an embarrassing amount of money on art school, and fortunately for everyone, I am just that type. Because of that, I have certain tools at my disposal, one of which is knowing how to digest, explain, and critique art. I know that explaining what you like about art and why you do can be tough, and it’s easy to feel like you’re out of your depth when you have to describe something that you may have trouble articulating. That’s why I put together this little guide to discussing, critiquing and thinking critically about comics art. It may get a little convoluted, and it may even read as a little pretentious at times, but the entire purpose of this thing is to help everyone understand, and therefore react to, comic art in a more informed manner. Comics are, after all, a visual medium. So we should be able to discuss art in a way that doesn’t rely on narrative or hyperbole, right?

I. Objectively Viewing Art: An Introduction

Art, by its very nature, is meant to provoke discussion. When an artist puts lines on paper, it is with the intention of stirring something inside of you. Whether your reaction is positive or negative doesn’t matter as much as some people think. The whole point is to make you feel something. Does the art grab your attention? Do you feel compelled to react to it? If the answer to either question is “yes,” then the artist has succeeded, even if your reaction is to say, “This is awful.”

It’s my opinion that if you’re going to engage in a conversation about comics art, then you should be able to get a little bit deeper than a declaration of whether or not you like it. If there’s something in you that compels you to comment on art, then let that compulsion run free by arming it with the language and insight that’s needed to really make your point understood. Even if the person you’re talking to disagrees with your basic premise, you should at least be able to understand why you feel the way that you do.

Continued belowWhen preparing to discuss comics art, there are a few basic things that you want to consider:

- Does the art clearly define the action? This may seem a little broad, but you can ask yourself things like: do characters magically appear in the room? Is someone suddenly holding something they weren’t before? Stuff like that.

- Do you know which characters are which? Does the protagonist look completely different in a ¾ view than straight on? Is it clear who’s who? Is there variety in character design, or does everyone have the same face and different haircuts?

- How’s the word balloon placement? Is it clear who speaks first in a scene? And does the lettering have room to breath, or is it all jammed in the corner of the panel?

- Where are we? Any hints as to whether or not we’re inside or outside? A secret laboratory or an office in a high-rise?

This isn’t an end-all-be-all list by any means. It’s just intended to get the ball rolling on how you digest and consider comics art. We need to ask ourselves questions like these for one very, VERY important reason: as a critical thinker it is crucial that you make the distinction between art that you don’t like for personal reasons, and art that you don’t like because it has technical failings. I’ll tell you right now, if it’s released by one of the bigger publishers (think Marvel down to Oni), the instances of ‘this art is just not for me’ will happen far more often than ‘this art is bad.’ If it’s clear that someone’s art is technically proficient, but does nothing for you, then it’s unfair to dismiss it outright. Part of critical viewing and discussion is giving credit where it’s due and acknowledging both pluses and minuses in your assessment. That’s the nature of a critique.

Critiques are crucial to the discussion of art. A proper critique will weigh the positives and negatives of a work, and use that to determine whether or not the piece is successful. This is a personal decision! Two people can see the same piece of art in completely different ways, and therefore judge its qualities differently. Neither will ever be wrong, especially if they can articulately make the case for their view. Also, this may sound obvious, but it’s perfectly ok to like art that has technical failings, but that doesn’t mean you should ever avoid discussing what’s wrong with it. It’s not unlike saying, “I love Coca-Cola, even though I know it’s a slurry of chemicals I probably shouldn’t have in my home let alone drink.” Acknowledging that the art you enjoy is not perfect is your responsibility.

Far too often, people will weigh the merits of a comic based on its narrative, while paying little to no attention to the art. This is a visual medium, so the art should be a crucial part of any discussion on the success or failure of a comic. Now, can you debate whether or not Morrison’s interpretation of ‘The Killing Joke’ has merit without ever mentioning Brian Bolland? Sure. I mean, I’d rather you didn’t, but you could. But if you’re discussing whether or not you like that book and never bring up Bolland’s contribution? Then you gotta ask yourself what you’re doing.

II. Now We Can Really Get Started

First things first, let’s state the obvious: we will never all be in total agreement about what is and isn’t good art. And, of course, that’s a-ok. It would be super boring if we all liked the same stuff and then the internet would go away. Now here’s the rub: you can’t just say, ‘this is great,’ or, ‘this art is terrible’ and expect to have a real conversation around that. I mean, you can, but that’s not being realistic. If you are going to make declarative statements, be they positive or negative, you should be able to follow with a considered argument that enforces your position, and be open to hearing why someone else may feel differently. Discussing art should never be about swaying someone else’s opinion, but about presenting your thoughts in a way that lets others understand your position. If what you say makes someone look at a comic differently, then let it be because you presented a strong argument, not because you shouted them down.

Continued belowSomething I see a lot of, and this is everywhere, are statements like, ‘Artist X is off their game,’ or, ‘this looks amateurish.’ If you’re critiquing a comic, or any type of art really, then I’d argue that you have to begin by giving the artist the benefit of the doubt in regards to intent. No artist wants their name to be associated with shit work, so start with that in mind. Am I saying that you should always conclude that everything is intentional and that no one ever phones in a job? Of course not. My point is that you should never start from that position. Look for the context of a work and let that be your guide.

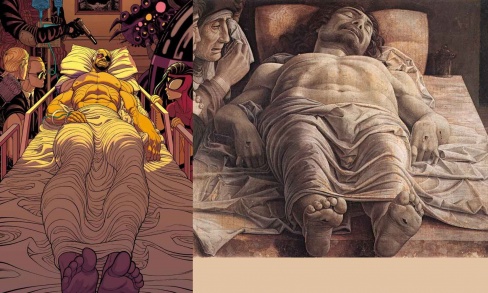

Let’s take this piece by Ben Marra as an example. A harsh, snap criticism of this image would be that it’s amateurish, disproportionate and has an unrealistic rendering of perspective. In a vacuum, that is all true. But no art has ever been produced in a vacuum and therefore can not be judged as if it has. So let’s examine this piece a little more. What are some obvious influences at play here? Straight away we can see that Marra’s probably very influenced by Jack Kirby by way of Rob Liefeld. You can see this in the way light is rendered on fabric. I’d also say that there is probably a sprinkling of ‘70s underground comics and ‘80s crime-action movies in there. It’s also plain to see that Marra draws inspiration from renaissance painting. Let’s compare his piece to Bernardino Luini’s Madonna and Child Enthroned with Angels. Look at the way the seated figures in both images are rendered. It’s almost as if none of their chairs are right angles, right? Like they’d slide off the seat if they picked their feet up off of the floor. Also, and this is something that can certainly come from Liefeld’s influence as well, the proportions are all wacky. Heads and torsos are enlarged, feet and hands look smaller than what’d be natural. Here’s my favorite example of warped proportions in renaissance painting: Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck. Look how insane this thing is.

First off, if this Mary stood straight up she’d probably be 12 feet tall. As the title suggests, her neck’s long, but so is that hand. Compare her hand-to-face ratio to your own if it’s difficult to make out. Then consider the length of her legs. All of this is, by comparison, making that baby Jesus out to be about 6 feet tall. Oh, and the way she’s sitting is pretty similar to the last piece we examined, isn’t it? Madness. Now let’s jump back to Marra’s piece. He’s playing with a lot of the same ideas, but in his own way. Perspective, proportion, composition…it’s all there, and I firmly believe that what he’s done is absolutely intentional. He could draw a perfectly rendered human form if he wanted to. Same with perspective. But he’s bending these elements and leaning on his influences in order to say something. This is what I view the context of the piece to be. Now let’s get to intent.

Why would Marra do this? What is he saying? Now unless you have a direct quote from an artist, you’ll never be able to definitively tell others what the intent of a piece is. So we speculate. And that’s ok; it’s what people do with art. It’s why the Mona Lisa is still discussed. So Marra’s intent? My guess is that he’s reacting to the common, yet diminishing, notion that comics are a crude form of art. He’s pushing back against the notion that comics are the medium of adolescent boys’ fantasies by creating art that looks to be all of that on the surface, but is actually a deeply informed and quite high-minded piece of work. Can I be overshooting the mark? Am I seeing more meaning than Marra consciously injected into the piece? It’s possible. But we’ve seen enough evidence to show that the theory of his intent is probable.

Continued belowIII. Building a Foundation

“Holy shit, is this guy really talking about comics as they relate to 16th century art?” the entire Multiversity audience collectively pondered. Yeah, I am. Or was. I think I’m done with that. But now that we’ve gotten through it, we’ve arrived at our next stop: you have to consume art to be able to discuss art. I’m not an art historian, and my interests don’t necessarily lie in the Italian Renaissance. But I’ve exposed myself to enough of it to recognize its influence when I see it. Comics as a medium is really interesting in that artists can have an immediate influence on one another. An artist could see a comic that changes the way they think about their craft and have something new that reflects this fresh influence posted online that day. This is sort of unique in terms of visual art, because it tears down the notion of ‘schools,’ and creates a constantly evolving and shifting creative landscape.

So, since contemporary artists influencing one another is always happening, it’s pretty important to digest as many different comic artists as you can. How often have you heard someone say, ‘Artist X seems to have a lot in common with Artist Y?’ It becomes easier and easier to make these sorts of comparisons, which help you discuss what you’re seeing on the page if you actively seek out the work of artists that are new to you. And not just the artists you like. You need the comics artists you don’t like, too. That ‘bad’ stuff is actually the most helpful, I think. You also need familiarity with and understanding of as many other forms of art as you can stomach. Observe as much commercial art as possible, too. Most comics actually have more in common with commercial art than fine art. The deadlines, the marriage of text and images, the disposable nature of it all, these are qualities you find in print advertising, as opposed to what’s hanging at The Met. So look around you while gliding through your daily routine. Ads on mass transit, billboards, the chalkboard at that hip little cafe you like, logos, calligraphy; all of this will help you become a more informed consumer of art, if you look at them critically. And like those comics artists, looking at the stuff you don’t like – the ‘bad’ stuff – is really helpful, too.

So why do I keep talking about ‘bad’ art being helpful? Simply put: you’re less emotionally invested in art you do not like. When you’re truly moved by the marks another human being put on paper, it’s powerful. They’ve touched something inside of you that you may not have even known was there. ‘Good’ art teaches us about ourselves and speaks to our personal experiences. So, that said, there can be a lot of things that you need to unpack before you can rationally explain why Quitely’s art in “We3” makes you weep uncontrollably. But the stuff we don’t like? We can see that for what it is with much less effort. We can analyze it without injecting ourselves into the middle of it. And because of that, we can strip it bare and give it a good, clinical once-over that’s unencumbered by sentimentality or nostalgia.

So look long and hard at the subway ad for discount dentistry. Think about the terrible illustrations that adorn so many off-brand cereal boxes. And drink deeply from the well that is Greg Land. It all helps. Promise.

IV. Understanding Process

When critically discussing art, a basic understanding of how the art was created is important. If you’re not familiar with how comics art is made, I’d remedy that post-haste. There are countless practicalities and limitations that are inherent to the medium that have contributed to its aesthetic. Pre-digital comics were made in a way that was dictated entirely by the printing process. Pages of original art were shot on a photostat machine that could only see black or white, which is why we have inkers. The art needed to have bold, clean lines in order to be reproduced. Color had to go through a fairly labor intensive color separation process. The masthead and bullet on every cover had to be pasted up. Word balloons had to be placed and ruled for lettering.

Continued belowAs we’ve transitioned into modern comics production, a lot of the process has remained pretty similar, despite no longer being subjected to the analog limitations of yesteryear. It’s not uncommon for the penciler, inker, colorist and letterer to all be different people, even though we have the production technology that’d allow one artist to do it all themselves. Sure, in some cases production schedules will dictate how many hands are involved in the creation of a comic, but a lot of the time it’s probably more a matter of artists wanting to work in a traditional way. You’ll see that this has changed, though, with more and more pencilers choosing to ink or color the art themselves, and personally choosing their collaborators instead of having one assigned by an editor. Understanding how many people have gone into the production of a comic is important. If there is an aspect of a work that you feel is particularly strong, or helps enhance the reading experience, then the person who did that should be recognized. It’s easy to imply that all art credit goes to the highest billed artist, but that’s lazy. Simonson’s “Thor” would not be what it is if it weren’t for Workman’s letters, in particular his sound effects. Dave Stewart enhances every page of “Hellboy” with his color choices and techniques. Let’s give credit where it’s due.

The converse holds true, as well. If someone on the art team is not up to the task, it can bring the entire book down. In a lot of instances, it would be unfair to condemn the whole of a creative team for one lackluster art element. If you have a thorough understanding of process, then you should be able to recognize when there is a weak element affecting the rest of the work. Is the inker not representative of an established penciler’s voice? Does the color palette muddy up otherwise solid line work? Is the kerning of the letters loose or uneven? Are word balloons or sound effects intrusive? Or maybe they clash with the art style? The ability to see the anatomy of a page will aid you every time you’re searching out what does or doesn’t work about the art.

It is also important to familiarize yourself with the tools and techniques artists use. I’m not saying that you need to know which brand of bristol board Kirby preferred, but you should be able to discuss how a page was most likely created. Does that look like hand lettering? Is that ink wash and digital coloring? Stuff like that. Again, this is a ‘most likely’ situation. If you can’t be certain, that’s fine. But if we’re going to talk about art we’re going to have to describe what we’re seeing, even if we may be a little off the mark. It doesn’t have to be an end-all declaration, and don’t be afraid to make soft proclamations here. “It looks as if the linework is scanned right from pencils,” would be an absolutely acceptable statement to make if you were not completely certain if a page was inked or not, but it looks to you as if it may not be.

An easy way to gain a deeper understanding of process is to go straight to the source. What do the artist themselves have to say about the work? There are a lot of resources for this: podcasts like Tell Me Something I Don’t Know, Sidebar and Inkstuds will often go in-depth on art, where most comics podcasts are content to simply discuss narrative. Even here at home, Greg and I work hard to cover this stuff on Robots From Tomorrow, in both our interviews and book discussions (Jim Rugg said that his talk with us was the most esoteric interview he had ever done). You can also seek out process posts that artists have put together. Amy Reeder has done a number of them on topics like cover composition and color technique, and Todd Klein will often dissect lettering choices and techniques on his blog. Seeing the choices and minutia that goes into comics creation can often be enlightening and provide a whole new perspective on the craft. If you’re going to seriously think about comics art, it’s important that you seek this stuff out!

Continued belowV. Study

I know I said I was probably done talking about renaissance painting, but it looks like there’s going to be a little more of it. If you want to achieve true critical enlightenment then you’re going to have to do a little studying.

Composition is a huge element in comics design. In particular, I’m talking page and panel composition, and how the two relate to one another. This is the nuts and bolts of how a story is told in comics. If the composition is out of whack or not thoroughly considered, then the story will suffer. So, what’s this have to do with renaissance art? A lot. You see, a ton of renaissance art, Italian in particular, was dedicated to the idea of god and worship. Because of that, this is the period where you see the ideas of focus and direction become mathematical. Large, simple shapes are utilized to push the viewer’s eye around a canvas. Elongated triangles point to the heavens; wide rectangles anchor elements to the earth. Limbs and spears are used to direct and shift focus. The innovations from this era of art continue with us to this day and are surprisingly present in comics art. Makes sense, right? Comics rely on direction and motion to get you through a page and push elements to the forefront of your attention.

Often times, when a comic becomes confusing or you lose the thread of the narrative it can be attributed to the ‘flow’ not working. Somewhere the art failed to deliver you to the page turn. This is something Frank Santoro has gone into an almost maniacal level of detail on his blog.

SMH at any comics reviewer who doesn’t follow Santoro’s tumblr.

Studying the craft of comics shouldn’t end with technique and composition. As an informed reader you should also have a familiarity with as many different types of comics as possible, both narratively and artistically speaking. Look at work that is outside of what you’re familiar with. Don’t be satisfied with only being exposed to what your LCS carries and know that there’s always more out there. Have a look at the newly announced lineup of Retrofit artists. Download the Fantagraphics catalog. Look at Brian Chippendale’s comics. Just find stuff you didn’t know was out there. Find comics that visually push you to the limits of understanding. It’s like stretching! Feel the burn.

VI. What’s the Point?

What’s the point of viewing comics critically and, in particular, discussing the art of comics? It’s my opinion that you should be doing this to spur conversation and expose others to work that you love. And you should expect the same in return! What a world it would be if every Wednesday gathering at your comic shop of choice was a cacophony of well-reasoned discussion on the merits of that week’s bounty. Does that mean that every comic should be lavished in glowing praise? Certainly not. But is it good to be able to express what you perceive as successes or shortcomings in art? It certainly won’t hurt!

Now I’ll tell you what isn’t the point: needlessly shitting on an artist or their work or presenting your opinion as the only valid one. No one wants to be a part of that type of discussion. That said, it’s important I reiterate that we should never shy away from being critical of problematic work. But your approach to work that you’ve decided needs a less-than-pleasant critique should be well-reasoned and evidence based. Don’t be someone that relies on vitriol over substance. Instead, be the person who others look to for the real-talk.

VII. Resources

Vocabulary is important when talking about art, but the list of terminology is just too massive for us to get into here. So here is a short list of material that you can use to familiarize yourself with common terms and their usage:

Continued belowBook: ‘Understanding Comics’ by Scott McCloud

You should have this if you’re interested in discussing comics art. Read it, get to know it, but don’t take it as gospel.

Magazine: ‘Draw’ published by TwoMorrows

TwoMorrows is an infinitely helpful, infinitely underrated resource for understanding and discussing comics. I particularly like ‘Draw’ because of it’s dissection of the art form through discussions, interviews, and guest columns from a wide range of comics artists. I cannot recommend this magazine enough.

Video: P. Craig Russell’s Guide to Graphic Storytelling

Russell is a master of the form, and a few years ago he put together a series of videos breaking down his own work. Lots of composition and layout dissection! I think these are infinitely valuable. They’re scattered across YouTube in bite-size chunks.

In addition, your social media streams can be great ways to have a wide range of voices presented to you in a regular and fast way. Try and seek out artists who like to break down their processes.

At the end of the day, if this is something you truly want to do and improve on, you have to know that it is a never-ending process. I’ve been studying art for the last 15 years and still feel like I’ve only scratched the surface of what comics has to say and offer.

This piece was originally written as a sort of internal memo here at Multiversity Comics, with the intent to help reviewers who don’t have an art background discuss art in a more critical way.