At Multiversity, we love comics. Sometimes, love is complicated.

This is a story of why an Asian-American comics reader departed from Asian comics, and why he came back. My relationship with manga has been symptomatic of complicated relationships between culture and identity, reading and longing. But at some point, I had to ask myself those hard questions that come when we examine our implicitly-held tastes. Why did I avoid manga?

Sometimes, we fight as comics fans about representation and identification, creative control and cultural clashes, and with good reason. But with the hope that walking in each others’ shoes expands the empathy with which we engage in these dialogues… Come along, and I’ll tell you an odd love story, in three vignettes.

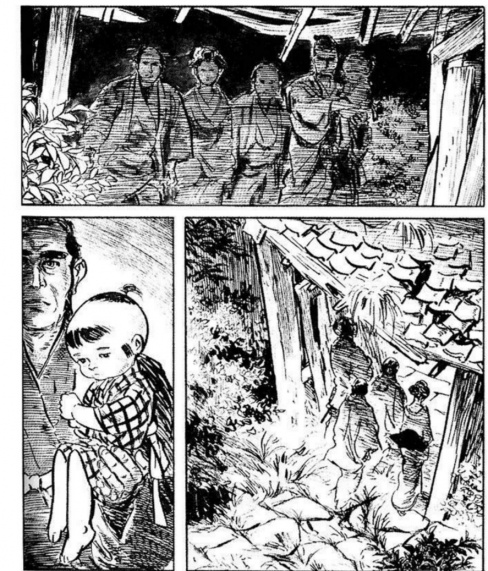

In the first, you’re a six year-old in Taipei, Taiwan, a Chinese kid standing in line in your itchy school uniform, and you have gnawing hunger. You’ve pocketed the thirty mao in coins your parents intended for you to buy a pork bun. Instead, you’re buying “Dragonball.”

Two years earlier, in 1984, Akira Toriyama had begun the series in Shonen Jump in Japan, and already ‘Dragonball’ had made the short leap to Taiwan where a transnational Chinese-American-Chinese kid like you could grow wide-eyed and spiky-haired obsessive about it, squirreling away lunch money to buy those books you’d wear down to mulch. You literally went hungry for those comics.

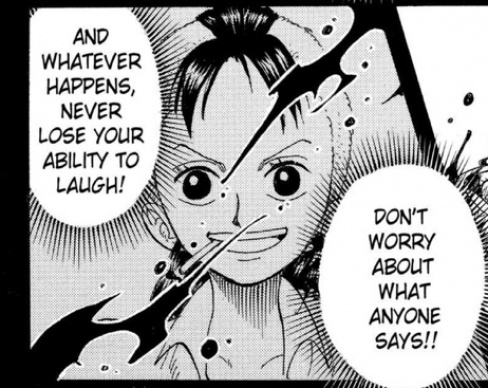

Goku’s drawn all over your homework. You’re furtively reading those books with bent spines long after lights-out by the flickering neon of Taipei streets through your window. He was a Monkey King, and so were you, born the Year of the Monkey, chubby armed, floating on a cloud, with a fist to subdue planets, dexterous as Cheng Long (who weirdly, six years later and an ocean away, would reappear as a movie star named “Jackie”).

In “Dragonball,” your dad’s folk/literary bedtime stories merged with cinematic fight tropes, video game quests, and the short-and-precocious sprite you saw in the mirror, brashly naive, pre-sexual, voraciously imaginative. You gobble it up, lunch be damned.

The second moment, one that’s probably been somewhat embellished in your memory, but real under your skin:

Now you’re ten years old, cusp of adolescence, standing helplessly in your Bart Simpson shirt under the California sun during recess, again with the gnawing hunger.

This time, though, you’re watching as your Chinese-American friends torment the recent Chinese immigrant girl (you whisper the fearsome label, f.o.b., but never out loud), who keeps hiding in her manhua instead of fitting in and playing gossip games. They taunt and jeer, and you’re not happy about it, but you’re silent. You sense that this perfectly sweet girl is the repository of Chineseness to your Americanized friends, who are flailing desperately for distance from your reviled skins. Around you, a ubiquitous cloud of white gaze.

She’s no shrinking violet, and she pushes back, resists, but your usually civil friends are possessed by some ritual spirit they must exorcise. They tug on her hair, mocking. They rip the Chinese tankōbon from her hands. Watch the wind blow torn pages across the school yard as she scampers to retrieve them.

Finally, you realize this is cruelty, and mount a flaccid defense, but you’re much too late for the playground-sized trauma and tears, and your friendship with both sides from then on is tinged with inchoate regret.

Oh yeah, and the gnawing hunger is because you’re still redistributing your lunch money to a comics addiction. But now, it’s Chuck Dixon’s Punisher meting out taxi driver justice, and it’s Breyfogle’s gray and blue Batman, and the scratchiness of Eastman and Laird’s TMNT, and those dog-eared Calvins and Hobbeses.

Once, when you’re reading your stack of those American comics on a trip, your cousin, a more recent immigrant from Taiwan, asks you why you read American comics. Weren’t Asian comics so much better, with something for every interest, with romance comics and basketball comics and tentacle fetish comics?

Puzzled, you reply, “but look at this variety! This one has a cape, this one doesn’t but kills people, and this one is a detective without a mask, and this one is funny animals fighting in masks. Look.”

Continued below

Truth be told, my childhood dreams swirled with pages torn out and blown away by Western winds, erased by my new Wednesday ceremonies of US comics: emotionally projecting onto costumed underdogs, estranged and alienated, mischievously and virtuously anti-authoritarian, externalizing pain with violence. I tossed nights imagining my righteous revenge against the white bullies at school. But I could not see the shame or self-disavowal on the other end of that violence, the cringe we had developed at how noisy our parents were, other kids’ revulsion at the odors from our lunches, or comics others couldn’t read because they go backwards and even then still don’t make any sense.

At this point, I feel urgency to declare that this is autobiographical reflection with a purpose. Please don’t get it twisted, dear friends: I ain’t conflicted. Decades of simpleton readings of hyphenated authors have left a trace in non-immigrant Americans that people of color, Asian-Americans especially, continually live torn between two worlds, and as a result suffer from endless insecurity and internal turmoil.

While there’s some truth there, the presumption of that conflictedness can become its own caustic stereotype. We all grow up within multiple cultures, we are all hyphenated somethings, and moments of self-realization of internalized shame aren’t invitations for others to find safe harbor for their prejudices.

And by the way, that girl with the torn manhua? Those Chinese American friends who taunted her? Now full-grown, they are proud, all very adept in multiple cultural worlds, competently and impressively Asian and American conscious intellectuals and transnational professionals. This story is not for pity or aspersions.

But I didn’t read a single Asian comic between the ages of eight and eighteen.

Third memory. You’re twenty-five, and hungry again. And still in school. This time, you’re an English teacher in the Bay Area, breathlessly keeping up with a Freshmen class of youth who also speak Spanish and Hindi and Tagalog and French, and they bustle with the energy of a globe within the tightness of your classroom. A quarter of a decade in these times in such a cosmopolitan area is enough to see significant cultural change, right before your eyes.

Sometimes, it hits you in the face. One of your favorite students, a quick-witted Mexican immigrant kid, stops you in your tracks when he grabs you with his reader’s enthusiasm: “Hey, teacher, you seen this before? A comic book of my favorite show. Dragonball Z. Heard of it? Hella cool.”

And something profound strikes you. In the intervening years, you’ve “outgrown” comics. Now you’re Wu Tang Clan, Hondas, and vegetables, and you’ve left behind WildC.A.T.S., Harvey Kurtzman, and Vegeta. You don’t skip lunch to buy comics, you got business to handle. But your Latino student’s immersion in the substance of your childhood dreams, two decades and half-a-planet away, confronts you strikingly with a long-buried and weird shame, suddenly transmogrified into a strange pride.

You remember reading “Barefoot Gen” in a college class. You start seeing Akira GIFs on Facebook. From Black friends. And it dawns on you that the false choices you made to leave comics in order to enter “the Culture” have come full circle, and the Culture isn’t what it used to be. Goku’s grown up, he has a son, he’s on an American lunchbox, and he looks like your childhood memories.

We gone global, you think to yourself.

When I read manga now, it’s an afternoon stroll with a rediscovered half-brother. It’s delightful, awkward. I recognize fragments of myself, and stare quizzically at what seem like oddities without any need to other-ize. Still not down with tentacles, but I can thrill at speed lines, laugh at random props appearing for sudden sight gags, empathize with the vexation that pops hashtag veins on foreheads.

We read comics, and read them to the point of gnawing hunger, to work out our internal stuff, the stuff of desire and shame and fear and glory, to release and enact the junk buried in our cultural souls, where we search for ourselves and the worlds we want to see around us, the heroisms and comeuppances, triumphs and confessions.

And if I allow myself some harsh light on my inner id, I must confess those choices involve some inclusions and exclusions we might rather not confront. Beside the indelible imprint of life experiences that make us, reside the panels of Tezuka, Ditko, Bechdel, Bilal, or Schulz, and they represent choices too, but ones we often make in fragile places, in subtle stages of our lives.

When we talk comics, we do well to remember: Yes, this is about funny books, about characters with no material existence beyond our paper and imaginations. But this is also about hungers, and dreams. This is about love.