We’re back with yet another installment in our series of year-by-year recaps of comic industry history. This week we’ll be looking at 1982. If you want a refresher before diving in, might I suggest you review 1980 and 1981?

Later in 1982, Jay Kennedy put together “The Official Underground and Newave Comix Price Guide,” the first book of its kind for underground comix. It featured a cover by cartoonist Bill Griffith showing comic collectors talking to each other amongst their collection. One of them is wearing a shirt that reads “Fanboy,” and this is the first time the word was applied to a comic reader (in print, at least). At the time it was a pejorative and universally considered an insult. It took a few years for fans to adopt the word as their own and apply it to each other in a more friendly manner. By 1999, it had been reclaimed to the point that DC printed a comedy miniseries titled “Fanboy.”

This was the year the direct market overtook the newsstand as the primary source of profit for Marvel and DC (or, if DC’s numbers weren’t quite there yet, the year the publisher accepted the shift as inevitable). Contemporary estimates in “Comics Scene” pegged the direct market as 50% of Marvel’s sales and 25-50% of DC’s. More modern estimates, which are farther removed but potentially better informed, say Marvel’s sale percentage may have been closer to 30. However, even at the low end of both, the profits from the non-returnable sales were definitely over the tipping point.

As fans took an outsized role in profits, they also overtook casual readers as the target audience. Both Marvel and DC released direct market-exclusive titles – “Marvel Fanfare” and “Camelot 3000” respectively – with higher production values that they felt fans would want. Publishers also took note of the direct market success of the alternative comic “Love & Rockets” by the Hernandez Brothers, which proved beyond doubt that an adult audience for comic material existed. Meanwhile, more young fans than ever wanted to become comic creators as the Joe Kubert School had its largest first-year class yet with almost 70 new students.

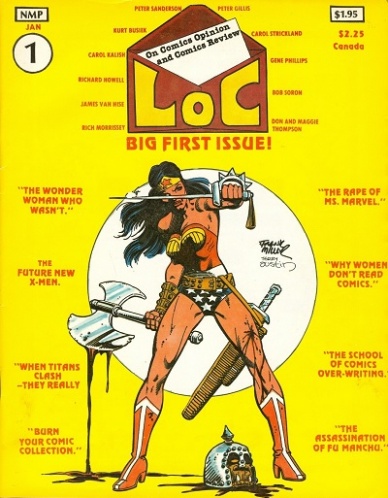

Companies other than comic publishers took note of comic fandom and its pocket book. Krause Publications bought the long-running fanzine “Buyer’s Guide” from founder Alan Light on December 1, 1982 and rechristened it “Comic Buyer’s Guide.” Krause brought in new editors Don and Maggie Thompson, who transformed it from an advertising hub to an information source. The west coast comic distributor Pacific believed demand for specialty stores outstripped their number and tried to lower the bar for interested individuals. Instead of a store front and all the associated costs, they offered to sell comics wholesale direct to fans for 20% off cover so those fans could resell the issues to their friends and neighbors. (As far as I can tell, this project never took off.) World Color Press remained the dominant player in comic production, as they were the only company offering letterpress, the least expensive method available to print a comic.

Continued below

Amid this booming, fan-driven market, the distribution side of the industry was experiencing a shock as one of the biggest players in the field, Irjax, had a meltdown. After spending the previous few years running an aggressive campaign to grow its market share, Irjax was struggling under the weight of its own success. One of Irjax’s methods to attract customers from its competitors was to offer the biggest wholesale discounts it could manage, which is how they found themselves running on a 2% margin in the early part of the 1980s – that is, if they bought material from Marvel for $1, they sold it to retailers for $1.02, who would sell it to readers for somewhere between $1.50 and $2. Irjax’s slim profit alone wasn’t enough to doom the company, so long as volume increased. However, the leaders at Irjax were so confident in their continued success that they started a publishing division as well, New Media. After finally admitting they had overextended, they were forced to close their distribution side in early 1982 and sell off their assets. New Media lasted only a few years longer.

As Irjax collapsed, there was collateral damage. Ijax had been in debt to virtually all of the publishers with whom it worked. Marvel and DC in particular lost big money. Retailers who had switched to Irjax found themselves scrambling to ensure they didn’t miss any product. Irjax’s biggest retail customer was Steve Geppi, operator of Geppi’s Comics World in Baltimore, Maryland. Geppi saw an opportunity and on February 1, he bought Irjax’s local warehouse and other assets. Through the purchase, Geppi inherited its staff and 17 retail clients. He named his new distribution business Diamond, and over the next few years he turned his company into a national supplier through a series of acquisitions.

Life was changing for retailers as well, though not as drastically. The advent of comic specialty shops had been driven by the large number of fans who were seeking back issues to fill their collections. Their needs had sat unfulfilled for so long that back issues had represented about 90% of a retailer’s annual sales. 1982 was the tipping point, as sales began to shift toward new issues. This sea change was slow and uneven, but also inevitable. Since these same retailers enabled readers to obtain every new issue they wanted every month, fewer collections had holes that needed to be filled, and demand for recent back issues dropped. Where retailers used to order high with the expectation that unsold copies would move eventually, they found themselves transitioning (over the next decade) to the moving target of 100% sell through.

On the publishing side, the entry of new publishers like Eclipse and Comico was balanced by the collapse of Harvey Comics. Upon learning of Harvey’s demise, Marvel looked to fill its shoes with a line of all-ages humor, but distributors convinced them the direct market was only interested in superheroes. Donald E Welsh balked at that and founded the Welsh Publishing Group, which had a strong focus on licensed magazines for children.

Marvel launched its graphic novel program in 1982 with “The Death of Captain Marvel.” Its writer/artist, Jim Starlin, had been able to negotiate better than standard terms for himself following his success with his earlier graphic novel, “The Price,” which was released through Eclipse. He wasn’t the only creator to find himself on better footing with publishers, as fan followings continued to give industry stars extra clout. Mike Friedrich tried to play the middleman in this dynamic when he became the first agent in comics in 1982, but his business was slow until later in the decade.

Not all creators were that lucky, though. Marvel Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter felt his bullpen was so weak in some areas that he organized internal classes on writing to help his staff improve.