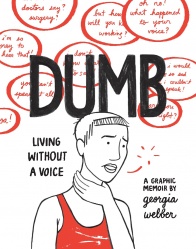

“Dumb” from Fantagraphics is the story of a throat injury that consigns its author, Georgia Webber, to six months – at least! – of silence. And what seems at first like an inconvenience becomes a de facto disability, touching every aspect of her life.

Written and illustrated by Georgia Webber

Dumb’s protagonist Georgia lives the relatively carefree and ordinary life of a twentysomething in Montreal: working at a café, volunteering at a local bike co-op, and going out on the town with friends. But when a sudden unanticipated throat injury forces her into months of silence, her life is thrown into disarray.

Part memoir, part medical cautionary tale, Dumb tells the story of how the book’s author copes with the everyday challenges that come with voicelessness. Throughout, she learns to lean on the support of her close friends, finds self-expression in creating comics, and comes to understand and appreciate how deeply her voice and identity are intertwined.

Full disclosure: this is a Montreal comic (although I didn’t know that when I chose it). Some of the references are highly specific, from the florist on Bernard to the wise-cracking receptionists at the Concordia student clinic. But, unlike a lot of Montreal comics, which use setting as a garnish, the sense of place winds up underscoring the message. This is a city where language is always a factor, and between regional accents, slang, third languages, and not knowing what your interlocutor is most comfortable with, communication can be a struggle. But: people always figure it out. And so Webber takes heart; maybe she can figure it out too.

Getting her point across in everyday life isn’t the only issue, though. People are starting to see her in a different way, as someone to be helped constantly. Then there’s the disturbing realization that some people find her silence attractive. Pair that with the fact that people find it easier to read her lips when she’s wearing red lipstick, and you’ve got the makings of an identity crisis.

And crisis really is the word that comes to mind when you flip through the book’s pages. It’s not a beautiful book, at least not at first glance. It’s alive with scribbles in black and red, layered over and over with handwriting that’s not intended to be all-the-way legible. There are speech bubbles that bleed off the edge of the page, that devolve into scribbles from one panel to the next. Sometimes it all resolves into order long enough to describe a street for us – the winding staircases of the Plateau are there, and you gotta fill that quota to be a Montreal comic – but the second we step back into the world of the mind, it’s chaos again.

That’s not to say this comic is hard to understand, though. Webber’s got a handle on the chaos, using it strategically. If a conversation is illegible, it’s because the content isn’t as important as the fact of the conversation in the first place. Misunderstandings and frustrations are tangled things, and they always come up tangled on the page.

Through it all, the character of Georgia is simple, clear, and true; a face drawn in as few lines as possible, and spanning a lot of emotional range, from frowning at an over-enthusiastic ASL interpreter to hamming it up to try and make herself understood.

One neat device Webber uses is having the figure of Georgia split off into two people, one in black lines and one in red, who confront and support each other non-verbally as we move through the narrative. Sometimes these are the only clear elements in an otherwise messy page. The emphasis here is on Georgia having to “split” herself, inhabiting a different persona as her lack of voice forces her into another way of being.

The secondary characters – Georgia’s friends and doctors – are constant and recognizable as well, with the sunny speech-language pathologist in particular coming through so strongly it’s almost like you can hear her. You come to know everybody and their varying degrees of helpfulness or comfort or feelings of home, even if you don’t always learn their names.

As the book nears its end, the narrative starts to cover the creation of this comic, folding in on itself as we realize that this is Webber’s chosen method of communication. We’re taken through the difficulties of writing this comic in particular – having to draw yourself over and over, having to represent something as abstract as pain (she uses showers of tiny stars). It’s an interesting meta moment, and far from self-indulgent, it grounds the book and clarifies its intentions.

The thing about the ending is it’s not really an ending at all; it leaves us right in the thick of Webber’s process, of acknowledging and living through her struggle as well as learning why it has this particular effect on her mindset. Of course her voice is important to her; but it’s particularly important to her because she has a lot to say.

“Dumb” describes an exterior and interior journey with deftness and grace, avoiding any navel-gazing traps and keeping itself grounded in the reality of communication and miscommunication. It’s a remarkable comic, and in a world where speaking up is an increasingly loaded topic, it makes for a humbling dose of perspective.