If you’re searching for significance in Gene Luen Yang’s oeuvre, you need look no further than his very first page: A kid’s nose is pregnant with an alien. That’s the premise introduced at the start of Yang’s “Gordon Yamamoto and the King of the Geeks,” his first published comic.

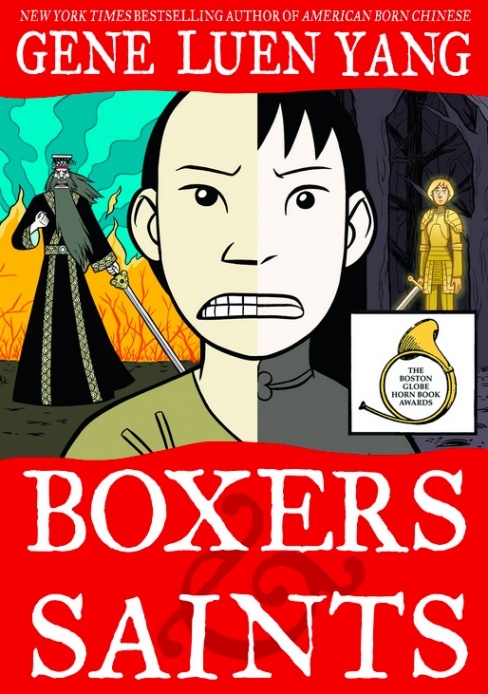

I’m not going to go digging too deep for profundity in a nostril with an alien lodged in it. It’s at least an excuse to draw a teenager sticking a TV coaxial cable up their nose to receive alien transmissions. Definitely, there’s a wealth of funny gems to mine in Yang’s books, his writer/artist turns in “American Born Chinese,” “Boxers & Saints,” and “Prime Baby,” or his scribing for “The Shadow Hero” (with Sonny Liew), “Eternal Smile” (with Derek Kirk Kim), “Level Up” (with Thien Pham), and his newest book, “Secret Coders” (with Mike Holmes), all published by First Second. I could elaborate on the Chekhovian comedy that marks Yang’s offbeat yarns of everyday characters, their silly tedium and exasperation with each other. I could contemplate Yang’s liberal sprinkling of fantastic, mythological, or simply comic-book-spiritualist elements, the space aliens, frog kings, legendary apparitions, and guardian angels, whose sudden appearances are unheralded but comically consequential. I could annotate the child-like/childish insult humor that decorates the various Bugs-and-Daffy or Wally-and-The-Beaver or Kung-Fu-Master-and-Young-Grasshopper relationships throughout his books.

But then someone would probably dunk my nerdy head in a toilet. If I was a Gene Yang character.

One dumb question I posed during my aforementioned lunch with Yang (you can read parts 1 and 2 of this 3-part longform series about Gene Luen Yang and his newest book, “Secret Coders,” but you don’t have to) was when I asked him to explain where his sense of humor comes from. I might as well have asked him to sequence his own DNA. How’s someone supposed to explain how they got funny?

He generously offers: “I wonder if it just comes from being a really awkward, skinny kid. People would always try to make fun of me for being skinny, and I would have to try to make fun of them back, right? And I remember getting kind of good at it, especially by the time I got to high school.”

A young, skinny Gene Yang mischievously retaliating is not a hard image to conjure.

“I had this friend who was much larger than me, and so often, our lunch periods would end with him just trying to chase me down and punch me in the face.”

Yang’s humor has that kind of quality, playfully poking, like the trickster Monkey of Chinese lore who shows up in both “American Born Chinese” and “Boxers & Saints.” It’s a humor that tends to rub out of the absurdity of juxtapositions, of funny and ironic things brought together, like Little Bao in “Boxers” encountering the strange physiognomy of a Western missionary.

Yang’s humor often suggests the hulking, hyper-pituitary giant-teen (a metaphor for life’s contradictions) is in hot pursuit, and he’s puckishly volleying joke bombs, half-survival and half-conquest.

And there I go, taking it all too seriously. Dunk. Flush.

Yang wonders aloud how seriously to take any of this.

In an afterword to “Loyola Chin and the San Peligran Order,” Gene Yang’s second comic, published in 2000 by SLG, he writes, “Is any of this going to matter in The End? (By ‘The End’ I really do mean the traditional Roman Catholic version of ‘The End,’ with all its pomp and circumstance.) Will my comics have any lasting impact on anyone or anything? Will my hand cramps and neck stiffness and psychological torture have been suffered for something meaningful?”

One gets the sense reading Gene Yang’s books that whatever goofballedness or “oh, comics” absurdity he might embrace, Something Serious always hangs like a specter, or maybe an anointing spirit, sometimes a Sword of Damocles, sometimes a Siren’s song. In “Level Up,” it’s reluctantly putting down the video games and picking up the med school scalpel. In “Saints,” it’s a Joan-of-Arc visitation and a call to spiritual arms. In “Shadow Hero,” it’s when the stakes of super-heroism hit sadly close to home, and the Green Turtle is pulled inexorably into saving honor, heritage, and community.

Continued belowBut it never feels right to jump right into the heroic or metaphysical or socially relevant themes in Yang’s books without continual reference to their cartoony quality, which let’s all agree to shed as a pejorative. It’s precisely the animating of every Chinaman stereotype in Chin-Kee next to the day-to-day travails of Danny in “American Born Chinese” that make it unique as graphic literature, something only-comics-can-do. “Boxers & Saints” attains a historically respectful account of the Boxer Rebellion exactly because Yang doesn’t treat his subjects with a cold scientific skepticism, as he accounts for their religious energies (yes, even the ones that contradict each other) as vividly as they believed them. As only comics could do.

That’s my argument for Yang’s artistic significance, not only within comics, but in terms of what comics mean within broader culture. When he began to self-publish “Gordon Yamamoto,” he named his brand Humble Comics, still the name of his website. “Humble Comics” is both a tautology and a funny contradiction, because what could be more humble in American culture than the tawdry Peter Pan-ism of comics (not my real opinion), and yet what’s more un-humble than declaring yourself Humble, capital “H?” There’s simultaneous earnestness, self-deprecation, and a winking smirk in Yang’s label. Not unlike his comics.

The artistic significance is that Yang keeps relentlessly holding together what common sense rends asunder. Comics can do serious business because they’re funny books, and therefore can maintain contradictions that just don’t float in other forms of culture. “Boxers & Saints” is a beautiful, structural example, a text of two interdependent halves, as is clear from the half-faces of the main characters on the spines of each volume, representing two contradictory points of view on the Boxer Rebellion seen through two intersecting human lives with two heartfelt stories of belief. Each of which Yang, the Chinese-American Catholic, shares sympathies with, and refuses to box apart.

Go ahead and look through Yang’s books for those same sparks that fly, comically and dramatically, when two sides of stark dualities are crammed against each other in narrative friction. Reality and fiction in “The Eternal Smile.” Escape and duty in “Level Up.” Heritage and adaptation in “American Born Chinese.” Then, reading the work and sitting across the table from their author, I’m struck by the mass of supposed contradictions, which are actually not, that Yang embodies. Asian and American. Computer Scientist and Storytelling Artist. Independent cartoonist and corporate hero fan. School teacher and nib jockey. Person of Catholic faith and champion of diversity.

The term “syncretic” pops to mind. In its limited use, the word refers to how peoples harmonize diverging religious frameworks (like Buddhist and animist, for example) into a mixed yet whole practice or belief system. But using the term outside of religion, I find Yang’s art exercising the syncretic cultural sense-making that comes out of those various worlds he inhabits and identities he holds. Sometimes, he straddles them. Sometimes, they humble him.

The straddling parts are aided and abetted by a unique publisher with whom Yang has shared a mutually beneficial relationship. When I ask Gene about his longstanding relationship with First Second, publisher of six (and with “Secret Coders,” now seven) of Yang’s books, he almost gushes.

“I feel really lucky I was a part of their second season, and I feel incredibly lucky to have found such an ideal home for me.”

Even before Derek Kirk Kim introduced Gene and “American Born Chinese” to First Second’s Mark Siegel, Yang had read and gotten excited about Siegel’s vision for the startup company. There is something pitch perfect about the partnership. As Yang describes it, Siegel is the son of a New York Jewish father and a French mother (two cultural pillars of comics), from childhood an American comics reader who could read French BD fluently and rubbed shoulders with Moebius, who envisioned a graphic novel line that had the color and stock of European comics, the size and breadth of manga, and the market, audience, and cultural appetite of an untapped segment of American readers.

“He himself exists between these worlds,” Yang says of Siegel, “and I think the company that he started does too.” Moreover, Yang points out, First Second manages successful entry into the trifecta of outlets, the book trade, library market, and direct market, that other publishers have not quite balanced with such finesse. Besides the market penetration, it’s the variety of audiences that First Second–and Yang’s books–reach that make the two so compatible.

For despite the warm praise Yang reserves for his Dark Horse, DC, and SLG partners, he admits, “I just don’t think I fit anywhere as well as I do with First Second.” It’s not merely a compliment to Siegel and the MacMillan subsidiary either, it’s a concession from Yang that the style and tone of his most personal work don’t quite neatly fit in either Big 2 superheroics or the indie world represented by publishers like D+Q or Fantagraphics.

You could make the case that First Second and Gene Yang have emerged together, fittingly un-fit, hand-in-hand. The publisher’s website announces, “we’re interested in authors with a unique and sincere voice. The books we love best leave us in a generative place.” The generative place, perhaps, where you defy categories and embrace the contradictions therein, producing something new and needed.

It’s fair to say that at this point, both Yang and First Second have emerged. “American Born Chinese” is on high school reading lists, “Boxers & Saints” in college Chinese history syllabi. “Secret Coders” is poised to find its way into teachers’ and kids’ hands, or maybe their handheld screens.

I have to confess a little regret that, with the further adventures of Aang, Katara, Sokka, Zuko, and Toph (if you don’t know those names, rectify that immediately!) simmering on one stove, with a de-powered and secret-identity-less Superman cooking on another, and more of Eni and Hopper’s coding adventures in the oven, it may be a while before we get more of those strikingly unique and personal pieces that I have so savored in my Gene Yang diet. Although an eight-pager in “Vertigo Quarterly CMYK: Black” with Sonny Liew was enough of an emotional gut-punch to sate me for months, I wonder if Yang’s prominence means he’s tied up with opportunities that preclude those humble, quirky, and very specific pieces of his that have stuck with me so hauntingly.

Yet for all that Yang’s forays into Chinese history or baby poop jokes or forgotten comics heroes have meant to me, I don’t look at his current workload of licensed titles and educational narratives as a retreat from what personally matters to him. Instead, they’re a maturation. Yang, who has beaucoup children, seems to be authoring less and less for himself, and more and more for others.

In some very candid reflections, Yang pondered with me “the danger for artists and storytellers to become really self-absorbed:”

“Because I could go all week now, now that I’m doing this full time [Yang recently ended his part-time work as a technology coordinator/teacher at Bishop O’Dowd High School], I could go all week without talking to anyone else. Just living in my own head.

“Maybe a hundred years ago, maybe there’s more of a sense for storytellers that there’s a metaphysical reality that you as an artist are trying to reach out for, to portray on the page. But now, the North Star that you use is not something external to yourself. It’s more about portraying something authentic to yourself.”

That feat is something Yang has achieved to great effect, for which many of his communities show him gratitude.

“But there’s a sense that your self changes a lot. And art can become a very internalized and self-focused thing.”

“Do you struggle with that?” I ask.

“I do. I definitely do. I think I struggle with humility in general. I’m good at the Asian style of humility, you know?” I nod, familiar with the public face of humility practiced in many Asian cultures, who perfected the humblebrag before anyone ever heard of such a thing.

“But the kind of humility CS Lewis [wrote about]: ‘true humility is not thinking less of yourself but thinking of yourself less.’ That I definitely struggle with.”

Continued belowI joke, “But that’s so hard. There’s so much good source material.”

All this talk about humility confirms for me the theme I see running around Yang’s stories. Yang’s heroes tend to be reluctant or unexpected ones, maybe best symbolized by “The Shadow Hero” protagonist’s super-power of not-being-able-to-be-hit-by-bullets. They all walk the hard road of humility, or humiliation. Whether Yang plotted it himself or with DC editorial, it makes solid sense that his Superman would be hamstrung of his infinite powers and find his fortress of secret-identitude stripped from him. It’s appropriate that Yang’s Aang the Last Airbender isn’t positioned to blast villains with shows of elemental force, but to broker peace and reconciliation in a reconstituted and fragile unity. It puts these heroes in a similar weakness as Four Girl, Gordon Yamamoto, Duncan, all of Yang’s heroes.

Heroism, if you wanna call it that, passes through humility. There’s no way around it in Yang’s books.

“Superman is always going to put others before himself. That’s his thing,” Yang declares, probably spoiling nothing. “If he ever stops doing that, he stops being Superman.”

“It’s kind of built into how we as humans understand what a hero is. There’s no culture that values selfishness over other-centeredness.”

Regarding Yang’s 2000 wonderings in the back of “Loyola Chin” about whether his comics have any lasting significance, it feels as though he’s surrendered those concerns to a Higher Judgment. Not because he doesn’t care whether his work matters; I would guess life’s far too complicated to make those determinations simplistically.

Let’s not overthink it. Stick the alien in your nose, and let’s get busy telling people some stories they need to hear.