Multiversity’s column of comic history returns with a snapshot of the comic world in 1991. This follows last year’s 1990 column.

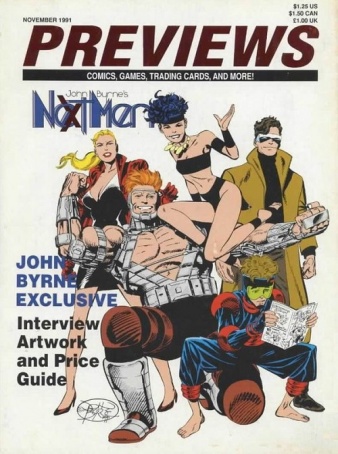

The year was a time of booming growth, excitement, and innovation. New books were arriving in stores every Thursday with an average cover price of $1.60, and annual sales exceeded $475 million. The number of comic specialty shops was increasing, boosted by the efforts of Marvel’s Direct Sales Manager, Carol Kalish. The new retailers now represented enough of a market unto themselves that the long running weekly newsletter “Comic Buyer’s Guide” split its professional news off into its own publication, “Comics Retailer.” Advances in printing technology made it profitable for more comics to abandon color separators, newsprint, and printing presses for laser printers and glossy paper. This fundamental change to production methods simplified the process and improved the product quality. The whole industry embraced cover enhancements, even the distributors. When John Bryne’s “Next Men” debuted from Dark Horse, it was promoted on the cover of Diamond Distribution’s “Previews” catalog with a foil embossed logo on the cover.

Other developments had a uniquely 1991 flavor. Selena’s Comics Hotline was a 1-900 phone number (that means it was a toll number, kids) that promised news, trivia, and other information about current comic books. Callers paid $1.95 for the first minute, and $0.75 for each minute after. I believe, but haven’t confirmed, that callers spoke to live operators and could ask about their specific interests, as opposed to a recording like DC’s hotline from 1976. There was also Comic Assistant, a catalog program from Huebner & Associates for your home computer that contained information and prices for over 7000 issues of the 150+ most popular comic titles. For just $34.95 plus S/H, you could receive this program on either 5.25 or 3.5 inch floppy discs. Hard drive recommended, updates available at minimal cost.

At the same time the industry was being revolutionized from the inside, the outside world was taking notice in a wave of “BIFF BAM POW!” style headlines.

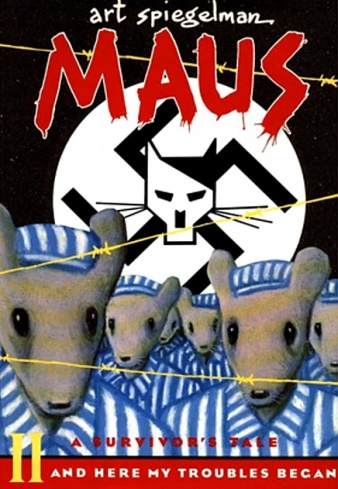

The first volume of Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” was republished as a trade paperback in 1991 to coincide with the release of volume two. When that second volume was published in late October, it became the first comic/graphic novel to be featured on the front page of the “New York Times Book Review.” This milestone in comic history is marred, however, by the first line of Lawrence L Langer’s review which effectively denies “Maus” is a comic. An equally skeptical, hey-can-you-believe-this “New York Times” article informed readers about the $82,500 sale of ‘an average copy’ of “Action Comics” #1.

Meanwhile, Neil Gaiman won the 1991 World Fantasy Award for Short Fiction with “Sandman” #19. When Gaiman insisted the prestigious writing award be shared by artist Charles Vess (and when real writers objected), the WFA rules were rewritten to specifically exclude comics from being considered in the future.

In a more accepting circle of media enthusiasts, former EC publisher Bill Gaines was awarded “Best Publisher” in the second annual Horror Hall of Fame TV special.

Encouraged by this popular recognition, Michigan State University librarian Randall Scott wrote “Comics Librarianship”, a how-to manual for cataloging, storing, and preserving comics in a library. Scott is an expert on the topic, being the founder and head of the MSU special collection of comics since 1970. Being the first such collection anywhere, he personally designed the catalog system for comics used by libraries around the world. By 1991, the MSU collection had over 70,000 pieces, many donated directly by publishers.

Everything important about Marvel in 1991 was centered around the company going public. Revenues and profits had been soaring since business tycoon Ron Perelman bought the company in 1988. In just two years, the company’s profits had doubled. This came through a strategy of increased volume, gimmicks, and price hikes. Bonuses and other incentives encouraged editors and creators to embrace questionable excesses.

Marvel listed 3.5 million common shares on the New York Stock Exchange in June 1991, valued at $16.50 per. SEC restrictions meant trading couldn’t begin until July 16, and the event was commemorated with an actor dressed as Spider-Man ringing the bell to start the day. He stuck around to visit with brokers through the day. In its prospectus for investors, Marvel narrowed its target audience to boys between 12 and 16. Just a few short months later, the stock price had doubled on the promise of a Spider-Man film written and directed by James Cameron, as well as the record breaking sales of Jim Lee’s “X-Men” #1 in October.

Continued belowBy the time Marvel released their first quarterly earnings report on October 21, net annual income was up to $6.7 million, well over the $5.4 million from the prior year. To keep the money rolling, Marvel converted books selling under 100,000 copies from newsstand to direct market only. In December, they raised most of their cover prices by $0.25, eliminating all of their $1 titles.

Where did all this cash go, aside from Perelman’s pocket and staff bonuses? Well, the Marvel office got its first computer in 1991. They used it for typesetting.

Seeds of Image

The formation of Image Comics may have been announced in February 1992, but its story began much earlier.

Throughout 1991, Rob Liefeld grew increasingly unhappy with Marvel. Malibu had been planning an “Art of Rob Liefeld” compilation book, but had to cancel it when Marvel and DC declined permission to reprint material from their comics despite previously allowing it for other artists. After Liefeld’s artwork boosted sales of “New Mutants” #100 to a million copies, Marvel polybagged the first issue of the followup series, “X-Force,” with trading cards. Although that gimmick rocketed orders to four million and earned Liefeld a $900,000 payday, he felt the increased use of gimmicks was being used to draw attention away from creators.

At SDCC that year, Liefeld was talking with Malibu publisher Dave Olbrich about projects aside from the canceled art book. Olbrich promised to publish anything Liefeld wanted to put out, and then extended that offer to any artist Liefeld wanted to include. Before long, Erik Larson, Jim Valentino, and Todd McFarlane were on board. When Liefeld advertised the book that would eventually become “Youngblood”, he received a call from “X-Men” editor Bob Harras threatening a lawsuit. Liefeld backed down to maintain a working relationship with Marvel, but felt Harras’ threat was frivolous and unlikely to be successful.

McFarlane’s last work for Marvel was the September issue of “Spider-Man.” His cited reason was a request from editors to redraw a violent panel to ensure CCA approval. The change was insignificant, but was described as the final straw. Considering the timing, McFarlane was probably just looking for a reason to leave and do his own thing.

Around October, Starbur Home Video released a series of VHS tapes titled The Comic Book Greats. In each video, Stan Lee interviewed a modern creator. The first volume’s subject was McFarlane. The second volume was Liefeld. The fourth volume was McFarlane and Liefeld together. Take a look at this ad, which prominently featured Spawn seven months before the first issue of “Spawn” dropped. (Also months before “Malibu Sun” #13. Sorry speculators!)

McFarlane wanted the group to make a statement with their departure from Marvel. If they left individually, they would be minor events that could be dismissed as creative differences or artistic prima donas. If they left together, it would make their position harder to ignore. On December 17, 1991, McFarlane, Liefeld, and Jim Lee informed Marvel President Terry Stewart that they were quitting.

The seven Image founders had worked on 44 of the top 50 selling comics released in 1991.

Other publishers

DC failed to make a splash in 1991. Their big crossover running through their annuals, “Armageddon 2001,” was supposed to feature the heroic Captain Atom taking a heel turn. Some of the hints they dropped early on in the story were too obvious, and before long Selena’s Comic Hotline was telling callers the twist. DC worried fans would be disappointed if they weren’t surprised, so they shifted course mainstream and changed the villain’s identity. The result was contrived and inconsistent with earlier hints, leaving fans upset and feeling cheated.

Midyear, DC licensed Archie’s Red Circle Heroes and tried to expand its juvenile audience with the Impact imprint. The line was carefully researched and focus grouped to be as appealing to kids as possible. After launching, it was mismanaged by editorial and shifting goals frustrated creators. The project failed in less than two years.

At the 1991 Capital City retailer summit, cartoonist Jeff Smith attended to promote his upcoming “Bone” series. Standing out as the only creator among marketers and vendors, he established many retailer connections that gave his black and white indie comic an early advantage. Over the next several years, the series became a massive success.

Continued below

Not every publisher thrived, however. Fantagraphics was still struggling to recover from the black and white bust a few years earlier, and their aversion to anything with mainstream popularity meant they weren’t taking advantage of the new boom. Instead, it chose to open a new imprint, Eros, and experiment with pornographic comics. This was a success, in part because of Diamond’s then-recent decision to offer an adult supplement to the regular monthly “Previews” catalog.