Lettering – adding text representing speech, thoughts, and sounds to images – is much older than the modern comic. It was an invention of political cartoons, and was a natural progression of an image’s caption moving into the image itself. Its first use is impossible to track down, but the method of putting words into balloons has been around for at least 270 years.

An example from 1762 can be seen to the right. Note the crudeness of the balloons in both shape and orientation. The forms are wavy instead of smooth. Instead of being a planned part of the image, they conform to the negative space in awkward ways to prevent obscuring any details.

The oddest thing about the balloons from a modern point of view is the lack of a distinct tail. Instead of having one, the balloons taper toward the speaker. This is especially noticeable on the left. How much better would this image look if that balloon and text were horizontal above the crowd instead of running vertically? The introduction of tails made it possible to better organize the balloons both for readability and clarity – by stacking balloons atop one another, it is very obvious which one should be read first.

It’s important to know that while lettering images is nearly three centuries old, it was not immediately the dominant form for cartoonists. The picture book method of alternating blocks of text with images remained in popular use well into the mid 1800s. The word balloon didn’t fully enter the public zeitgeist until cartoonists began using it for nonpolitical works. Multi-paneled comic strips first appeared in the 1870s, and the general nature of the humor helped to bring word-balloons to the masses. By the turn of the century, adding text directly to images was a standard practice.

To avoid sharing revenue, one cartoonist would handle all the production chores, including lettering. The lack of specialization limited the types of people who took the job – it was much easier to be successful with great art and okay handwriting than vice-versa. Often, the text in the balloons was just the cartoonist’s regular handwriting, perhaps with a bit more effort toward legibility. Cursive words were just as common as printed ones, and sentence-case lettering was probably more common than using all upper-case. (It’s hard to say for certain, given the small sample of available examples).

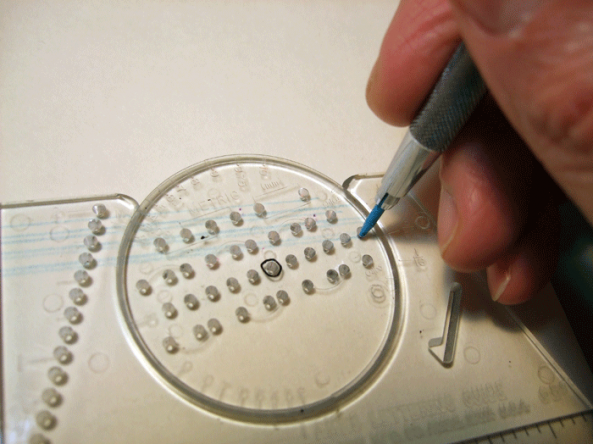

That changed in 1917 with the invention of the Ames Guide, a simple tool which made lettering in straight lines of even height a basic task. A fully illustrated how-to guide for the tool can be found here. It’s introduction instantly made comic lettering look far more professional. Its unchanged design remained in constant use for almost seven decades before being replaced by computer technologies.

There was an unintended side effect to the Ames Guide, however. Because of the extra lines a cartoonist would need to properly space the middle-height lower-case letters and any descenders (letter parts which hang below the regular baseline, like j or y), it was suddenly much more convenient for a cartoonist to uses all capital letters. There are many other arguments both for and against all caps lettering (enough to fill an entire up-coming article), but this is the reason the practice became popular in the first place.

The next big event in the history of comic lettering is only significant in hindsight – its impact wasn’t really felt until almost five years later. In 1933, the educator, entrepreneur, and printing salesman M. C. Gaines collected older comic strips and reprinted them in a free promotional booklet he called “Funnies on Parade”. This was the first comic book, and it proved popular enough to be followed in July 1934 by “Famous Funnies” #1, which sold on the newsstands for a dime.

This snowballed into a new industry with an incredible need for new material. Demand quickly overwhelmed the do-it-all cartoonists, and within a few years the act of comic creation had been broken down into separate processes which were handled in an assembly-line manner. By 1940, it was possible to make a living as a full time comic letterer. This new area of specialization would have an immediate and lasting impact on the look and feel of comics.

To be continued in The History of Comic Lettering: 1940-1990