Multiversity’s Lettering Week is nearly over, and you may have noticed there’s been lots of coverage about the profession, but not about the professionals. Here is where that changes. As part of the research for these articles, numerous letterers, writers, artists, and editors supplied some invaluable input. It seems appropriate to summarize the results for you, and in some cases share their answers with you directly.

Answers to the various survey questions were wide ranging in scope, but there was one thing all the letterers had in common: Not a single one intended to be a letterer. This shouldn’t be surprising. When kids are excited about comics and want to pursue them as a career, there are three obvious choices – be a writer, be an artist, and be both. Those are the most obvious aspects of the books, and the easiest to understand. It’s the pursuit of these roles that lead most of the participants in the survey to acquire degrees in design, and then other positions in the industry. When seeking to “break in” to comics, they jump at any open opportunity. In some cases, they take lettering jobs, and they discover a passion for it.

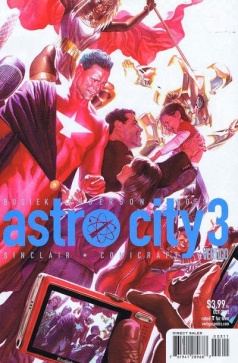

Once they have a job lettering, most of the interaction is with the editor. Depending on the company, a book’s letterer may change from month to month, making it hard for a writer or artist to establish a strong working relationship with them – communication is usually limited to notes in the script or with the art. There are some exceptions to this. Writer Kurt Busiek likes to work closely with his letterers, and Comicraft has been receiving creator credit on the cover of his “Astro City” for years.

While a consistent letterer would be preferable, IDW editor John Barber describes switching a letterer as “the least-disruptive change in a creative team.” This is in part because of style guides. In the case of Marvel and DC, it’s a house style that applies to every book. At others, like IDW and VIZ, it varies from property to property. Digital lettering with ready made fonts also makes the staff change harder to detect.

Gaspar Saladino once said it takes at least five years to become a good letterer, which means all the responders in the survey have already paid their dues. The greenest participant was Ed Brisson, who’s been doing it for “only” 7 years. Most answers feel closer to 15 years, with John Roshell being the most seasoned at 22 years. Experience plays a large role in lettering than just in sharpened skills. Every editor and creator in the survey said they prefer to work with particular letterers. Unless you’re lucky enough to be hired on as a staff letterer, getting work has a lot to do with who you know. When asked how much effort goes into pursuing work, the answers unanimously went down as experience went up.

But how much work does a letterer do? This is a simple question with complicated and qualified answers. There are very few professionals who are making a living just lettering. With some exceptions, most letterers either have other roles in the industry or other jobs entirely. Answers ranged from averages of one to twenty books a month, with variations of up to eight books a month. Mark McMurray, who letters manga volumes for Viz, said over the last ten years his schedule has fluctuated between 17 and 100 pages a week!

Part of the reason for the variation is due to different pay rates at different publishers. Like artists, they’re paid by the page, not by the book. If a letterer gets work from multiple companies, they may need different amounts of work from one month to the next to have a constant income. Page rates peaked in the early to mid nineties, and have been declining ever since. One responder described it as a “race to the bottom” in terms of pay. Part of this is because of a misconception that it takes less skill to letter well with a computer, and that anyone who can type can do it.

When a letterer gets a script, the writer and /or artist will usually have included notes (either handwritten or drawn in) to indicate placement and balloon type. There’s still room for invention and creativity, and this sometimes results in surprises of both the happy and unhappy varieties. When asked, every artist, editor, and writer could remember a time when lettering had to be redone to make sure important art wasn’t covered or the mood was wrong, and likewise remember when a letterer made a decision that enhanced the whole page. Revisions are part of the whole process, and no one expects it to be done the best way the first time, every time.

Continued belowBecause of the letterer’s place in development, most of them said they feel like part of the team, but not like collaborators. Bongo’s Karen Bates described the role as “a silent partner, a necessity that is often forgotten.” Still, Ryan Ferrier said that of the people he’s worked with, everyone “has taken it seriously, and recognizes its importance.” Indeed, a majority of the writers and artists polled said they see letterers as collaborators because the bad or impartial lettering can destroy their work. Some noted the degree of collaboration is different, and Paul Chadwick summed it up best: “I’m not at the point where I’d surrender a share of the original art to the letterer.”

Unfortunately, the same skills that make them good at their jobs don’t quit working when they put their work down. At the end of the day, when the letterer goes home (or out, if they work from home), they’re surrounded by lettering everywhere – billboards, clothing, signs of kinds, and pretty much everywhere else, too. They notice it all, for better or worse. But for all the bad kerning and leading they see, Derron Bennet says sometimes – sometimes! – “ideas have sprung from a good billboard ad.”