Following Saturday’s Eisner Awards announcements at San Diego Comic Con, comics watchers’ commentaries will no doubt note that despite standbys like JH Williams III, Dave Stewart, and Darwyn Cooke, the industry is again spotlighting its diversity of subjects, audiences, and creators: “Lumberjanes” came away a big winner, Venezuelan artist Jorge Corona got Russ Manning Award-love, Cece Bell’s fierce and vibrant “El Deafo” got its props, and Gene Luen Yang beat out a whole field of writers broadening horizons like G. Willow Wilson and Brian K. Vaughan.

This, along with the announcements of Marvel’s “All-New, All-Different” titles, the present-day divergences of the “DC You” relaunch (which I gather from the lineup means something like “there’s something for you, whoever you might be”), the inexorable expansion of the indie juggernaut at Image Expo last week, and the swelling rolls of cross-media at San Diego Comic Con, it seems a good time for this small suggestion about the state of comics.

Historians will quibble, but the eminent comics scholar Wikipedia reckons the Golden Age at circa 1938-1950, the Silver Age c. 1956-1970, the Bronze Age c. 1970-1985, and the Modern Age c. 1985 to the present. We are supposedly thirty years into this latest epoch of comics history, an era that has apparently lasted twice the length of the previous three. Maybe it’s time to recognize that we’re now in the middle of a different age. At the risk of sounding presumptuous, but emboldened by the Eisner winners, I tender this proposal: we are witnessing the Spectrum Age of American comics.

The Spectrum Age, I’ll throw out there, starts roughly mid-Aughts, and describes an era when what was once marginal in comics became mainstream, at the very moment when comics, an American popular culture medium of the margins, became radically mainstream. Put another way, the Spectrum Age marks the present period when, first, comics diversified in ways that their diversity, rather than their homogeneity, became their dominant characteristic, at roughly the same time that four states in the US and almost half its most populous cities became majority-minority (with no single racial group greater than 50% of the population) in the 2010 census. And second, comics have such a large presence in the American cultural imagination, largely due to cross-pollination with other media, but also because of the widening channels and formats of comics themselves, that what has often been a medium of outsiders now has an outsized cultural impact.

What I’d like to propose is that for roughly a decade, North American anglophone comics have been in the midst of a sea-change whose effects we can pretty much take for granted today, and whose aspects underlie most of the headlines in comics reportage, nearly every panel at a librarian’s convention or industry trade show, and a whole lot of the chatter between con-goers and comic shop denizens. It reverberates in campaigns to push comics forward, calls to come out of the fridge, hashtags crying out for diverse books, Tumblr posts fancasting the umpteenth future cinematic comics adaptation, forums full of fulminations and podcasts full of polemic and pleading. I choose to interpret the clamor not as signs of culture wars or partisanship, though certainly there are hard battles being fought with big stakes. But take a step back, and maybe it’s safe to declare: This era is when comics bucked the categories.

To be sure, comics have always been diverse, have always been “spectrum.” Since at least the Sunday funnies and its Four Color descendants, the sheer vitality and generativity of inky pictures and words on newsprint has spawned diversities—it’s endogenous to the wonderful attraction of comics that they push against imaginative limits. Since at least Herriman and McKay, comics have been proletarian and vanguard, mundane and underground, high art and lowbrow, kids stuff and instant dusty nostalgia, Jack Chick and Tijuana Bibles, all at once.

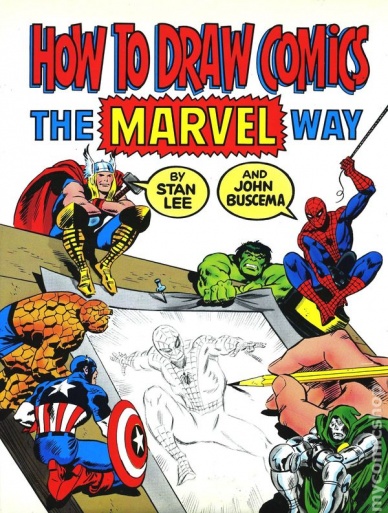

But the more that diverse comics wafted into cultural ubiquity, the more the homogenizing forces of dominant culture would lay claim to them, sometimes propagandizing them, sometimes Werthamizing them, delimiting them by Codes and Authorities that centralized and constrained the kinds of stories and representations comics could tell. The paradox in cultural phenomena where things are always pulling in towards uniformity and standardization but always simultaneously pushing out towards diversity and difference, what literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin borrowed from physics as “centrifugal” and “centripetal” forces, can be seen at work in the history of American comics. Conformity pulls in, diversity pushes out. Simultaneously, the Golden Age comic book loses inventiveness as superheroes reduplicate en masse, but Gaines in variety as audience tastes broaden. The same Silver Age year Marvel publishes a “How To” book for its house style to canonize the Buscema/Romita/Kirby of it all, Will Eisner births something new by drafting A Contract with God and consecrating the literary graphic novel with Eisnershpritz.

Continued below

Despite the market and industry’s sometimes ruthless strangulation of its creative people, their ideas, and their livelihoods, two things have always thrust comics in the direction of diversity: pen and paper. Pen, that words and drawings could always be wielded by whatever wunderkind or whackjob wanted to give birth to her or his imagination on a page. Paper, because the means and media of production and distribution of comics are always democratizing, from Gutenberg-style presses to GIFs, from photocopied comix to Photoshopped Comixology Submits.

So what makes these days any different? Wasn’t the Golden Age a “Spectrum” Age? And also the Silver, Bronze, and Modern Ages, weren’t they filled with space ducks and Black Panthers and Marie Severins? Yes, comics have always had diversity, just as they’ve always felt the hegemonic pull of monoculture, but my argument is that in the new millennium, comics passed a tipping point. The diverse energies that have always thrived at the margins of comics became their center, and we will look back on this time as the time when comics were not– could not be!– relegated to certain demos of readers, certain stages of life, certain kinds of stories, or certain breeds of creators. Perhaps we will observe this as the era that we became comics and comics became us, when the supreme court of public opinion flew rainbow flags for funny books, when we were all Hebdo or Groot or the 99 cent comic.

No, we haven’t reached the promised land. We are not yet satisfied with the quantity and quality of opportunities for artists and writers of “othered” voices and origins. The warp and woof of comic stories and representations still fall far short of the global range of identities, experiences, and perspectives that the increasingly diverse readership clamors for. And importantly, beyond questions of inclusion and tolerance, comics has a lot of unfinished business when it comes to apprehending and rectifying its part in perpetuating narratives and discourses of oppression, injustice, violence, and exclusion, sometimes even inadvertently while trying to dispense truth, justice, and some American way. Declaring a Spectrum Age is not an abdication of our ongoing obligation to upend cultural falsehoods, to broaden the tent, to echo people’s creative hungers for more just imaginative worlds, even the post-apocalyptic, horrifying ones.

“Spectrum Age” is not pronouncing comics as perfect in diversity, but planting a flag firmly in the era when our ethical prisms could no longer mistake white light for anything but the spectrum of colors that constitute it. Hard boundaries and tight categories are giving way to remixes and mashups, gender-bending and genre-blending, meta-fictional fourth-wall deconstruction and multiversal reassembly. I see significant change in four aspects:

Stories/Works. The comics themselves best display the phenomenon of a medium that has always been eclectic and diverse has now embraced its diversity and eclecticism as central. The easy examples spring from comics news headlines: the new Avengers team struts out Kamala and Miles and Thor (not “Man Thor”), tugging on the conscience of the still-WASPy and Wasp-less MCU Avengers; DC’s new Gotham-orbit features horror By Midnight and Hooq-ups in Burnside and Hermione-as-played-by-Damian and Helena Bertinelli, pushing the TV Gotham to liven up its streets. Meanwhile, as the heart of the Big 2 inches closer the shelves of indies and manga and mature comics, their diversity is becoming less consequential than the boom of new ideas, eye-popping designs, and surprising works that are valiantly remaking the image of comics shelves and setting off dynamite against Big 2 dominance with dark horse victories (see what I did there? …so ashamed of myself…). And then again, even the narrowness of where this paragraph started does disservice to comics’ current diversity. When I name drop the heterogeneity of protagonists and genres and story-types entailed in the Walking Dead, Naruto, Nimona, Fight Club 2, Fun Home, March, Captain Underpants, Lumberjanes, Hyperbole and a Half.. please don’t jump on me for what I’m missing on the list, because my point is that we can’t be comprehensive about what’s out there these days. Whatever expectations we had of what comics will top the charts, right now somewhere out there, the kickstarter post-apocalyptic sci-fi romance being created by trilingual SCAD students inspired by a combination of Daniel Clowes and Rihanna featuring a sexy anteater and talking donuts is revving up to be tomorrow’s Saga.

Continued belowYet I choose the word “spectrum” because it stays inclusive of the gold, silver, bronze, and modern (?) hues to which it owes its richness. Comics remain soaked with nostalgia even in their subversions and re-appropriations, whether you’re talking about the pulp-covered, Cthulhu-obsessed leagues of eighty-fifth retellings of Sherlock Holmes, or the excessive exposition of which segment of late ‘70s continuity was overturned by which crisis or secret war, or the insatiable historical/nostalgic itch Chris Ware and Seth and Grant Morrison keep scratching. It’s a medium whose exemplars are as generative as Youtube but as back-catalogued and longboxed as the Library of Congress. “Spectrum” does not mean novelty or kitsch or token; the raw materials in new comics recipes remain as old as dirt, even if it’s Vishnu reincarnated as Kanye West or Walt Kelly-style funny animals explicating Baudrillard. Or Archie doing everything. Today’s comic shelves are still replete with tropes, but when you scan them these days, doesn’t it feel like the tide has turned to Spectrum?

Media/Platforms. Then again, do we even judge based on shelves anymore? No disrespect to the LCS; as Mark Waid has said, digital has not so much poached customers from brick-and-mortar as expanded them, which my own buying habits confirm. But comics wedged their way into this century’s new media the same way no newspaper in the last century could do without an eight-page comics insert: webcomics, graphic novel imprints of major book publishers, small press distribution through Amazon, Diamond-beholden comic shops, newspaper strip archival volumes, digital comics on tablets and smart phones. (And yes, I still read Peanuts reprints in eight-page inserts in my local Sunday paper.)

It’s not just the growth of internet-age platforms, though, but comics’ saturation and infiltration in all media in a convergence culture. Again, cross-pollination isn’t new: early on, the popularization of your RKO serials and your Saturday morning cartoons went hand-in-hand with your Supermen and Orphans Annie. But take domestic 2014 box office grosses, dominated by Guardians and Winter Soldiers and X-Men and Big Heroes 6. Take your Michael Chabons, Jodi Picoults, Ghostfast Killahs, Chuck Palahniuks, Junot Diazes, and other literary luminaries, not to mention the George RR Martins and Stephen Kings that have always lurked near comics. Comics are everywhere in culture. It’s become a non-issue that we’re not seeing 90’s X-Men #1-type sales figures, because influence is up, development deals abound, indie darlings become streaming TV hits, doctoral dissertations are written in comics, hipster T-shirts and baby onesies sport Green Lanterns, and movies of video games of toys of comics characters voiced by actor-comedian-singer-writer Will Arnett make everything awesome for cross-licensing corporations. Now the fair comparisons aren’t 1990 Spider-Man #1 sales to Secret Wars #1 or Star Wars #1 sales, but to Pixar grosses, Game of Thrones viewership, Sims sales, Etsy traffic, Hunger Games imitations and fanfic, because comics blur and jump and jive with other media so adeptly. Or promiscuously.

I don’t think that means the Spectrum Age will be when comics lost their identity, because the warm center of what comics is and what the act of comics literacy involves is too hard to dilute or steal away. But gone will be the days when comics were cornered in people’s cultural imaginations to the ghettos of certain genres, certain kinds of retailers or spinner racks or bookstore sections. We can all shed a tear for the time when I handed a kid who had a Thor-themed birthday party a Walt Simonson book and he looked at it like it was homework. But it’s too late to be exclusive. Everyone knows about the party.

Creators/Community. In some ways, here, change happens slowly. This site’s own 2014 top ten writer’s list is an exclusive club of white males, though it’s certainly hard to argue with the worthiness (and perhaps even diversity) of their bodies of work. Yet the signing lines and panel attendance will be bursting this con season for the likes of Annie Wu, Phil Jimenez, Bettie Breitweiser, Karl Bollers, Noelle Stevenson, Axel Alonso, Sonny Liew, Afua Richardson, G. Willow Wilson, Khary Randolph, Kate Leth, Carla Speed McNeil, Kris Anka, Steve Orlando, Mariko Tamaki, Ramon Villalobos, Francis Manapul, Faith Erin Hicks, Ming Doyle, Jonathan Luna, Mahmud Asrar, Sana Amanat, tromping trails blazed by still-working legends like Kyle Baker, Ann Nocenti, Los Bros Hernandez, Stan Sakai, Lynda Barry, and I’m leaving out more than I can list.

Continued belowDisparities stay huge in the small community of creators. But the hospitality and openness of the comics creator community, notwithstanding alarming stories of harassment and glass ceilings, seems in the big picture to be tipping away from the good ol’ boys network to a more inclusive, collaborative tenor. The stories warm this Berkeley-based geek’s heart: Kelly Sue’s story of translating manga to hone her energetic and non-compliant writing and advocacy voice. Greg Pak working on Action Comics, kickstarting The Princess Who Saved Herself, coauthoring books about creative collaboration, and speaking up for diverse books. The Batgirl team’s candor and humility through fits and starts as a torchbearer. Let’s also not overlook the consciousness and complexity of comics writers and artists who do come from dominant groups, because what generation of cartoonists haven’t been folks on the fringes, prophetic outsiders in some respect?

And the gender, ethnic, linguistic, sexual, ideological, religious, socioeconomic, and other diversities bubbling up from the less-traditional sources and platforms of comics is still more promising. The real harbingers of the Spectrum Age are still building Tumblr followings and cultivating Patreon pledgers.

Audiences/Readerships. Change creeps into all fronts interdependently, but this aspect must be the biggest engine of change. The temptation is to think of this aspect only as a comics-buying market which has now opened up among new demographics. Even with those rigid bottom lines, the 53% of female Emerald City Comic Con attendees, shojo manga consumption, and the Reign of Telgemeier over graphic novel charts has spoken definitively. But I prefer to think about readership communities and sub-cultures, and how else does one describe the throngs of colorful cosplayers, Worst.Episode.Ever. pony-tailed forty-year-olds, and multi-generational families of fans now lining up for Free Comic Book Days and AnytownUSACons?

Once was a time when everyone read comics. So goes the myth. Whether or not the pure proportion of the human population reading comics has gone up or down, it’s hard to doubt their composition is profoundly different from previous eras.

So if this is an era, where are its endpoints? If the Modern Age is marked by watersheds like Watchmen and Love and Rockets, Frank Miller and Maus, how do we fix the landmarks of a move towards radical diffusiveness, comics springing out in a million different directions? How do we back-trace the tipping point?

May I humbly submit, roughly 2005 to 2008? A sampling of significant events, very certainly overlooking many important moments, but maybe a selection of things an outfit like TwoMorrows might document two morrows from now:

2005: Will Eisner passes, Batman Begins, Boondocks TV show, DC’s All-Star line and Darwyn’s New Frontier, Persepolis 2 published, Siuntres’ Word Balloon and iFanboy debut, the Eisners add a webcomics award, Viz Media forms.

2006: Marvel’s Civil War, Publisher’s Weekly ranks Scott Pilgrim as a top-three book, #Twitter, Jyllands Posten Mohammed cartoons protests.

2007: Fun Home, American Born Chinese, Minx line, Scalped debuts, Comixology launches, Hark! A Vagrant arrives, first SDCC pre-sale sell-out.

2008: Iron Man launches the MCU, Eric Stephenson takes over Image and Kirkman becomes partner.

Good arguments can be made for the tipping point happening at the turn of the millennium, or maybe even only the last three years or so. I’d say, though, by the time we get to Lumberjanes, Robbie Reyes, Non-Compliant, thenerdsofcolor.org, and Vivek Tiwary, we’re already standing on different terrain, wouldn’t you say?

For all the inclusiveness, there may be negative sides to this. We are locked in continual contentiousness about access, representation, and a market that has limits. We’re groping for mutual intelligibility, unity and coherence, a sense of mastery over the paradox of choice. Tolerance makes for weak bonds. Have we lost some minimum standards for entry into geekdom, or do we always toss aside fifty years of hard-earned story, investment, and continuity for the glitzy reboot aimed to entice any audience other than me, the loyalest reader? I think those are the deep-seated groanings we can hear, sometimes vitriolic on the internet, sometimes searchingly from true believers. Diversity is great, but shelf space is zero sum, and so are wallets and pull lists, bestseller lists and licensing deals. Will we get left behind by what we love?

Continued belowBut that’s why comics matter so much. In a market-driven world, they are the most populist of media, because they boil down to pen and paper (or Photoshop and PDFs), because they can come from writer’s rooms or corporate shills or an adolescent’s insane scribblings. I once asked Gene Yang at a talk he gave if being “the medium of outsiders,” as he called it, gave comics’ creators some implied ethical responsibility. Yang replied with a smirk (I’m paraphrasing) that throwing around a phrase like “ethical responsibility” with a room full of artists and cartoonists might be the wrong tack, but they would certainly speak in their work to what I’m getting at. As aesthetic choices and narrative arcs and twitter rants and editorial spats show: representations matter, cultures matter, these stories matter, and they have to do with everything we work, fight, eat, sleep, play, and love for.

And as our world struggles on for voices and stories from various places to take the stage, including the stages of our own beliefs and knowledges, fears and dreams, comics play a pivotal role in the cultural consciousness, a breeding ground of differences remixed, petri dishes of pluriform storytelling, the primordial stew of spectral images that transmit the world to us through glossy paper, pervasive screens, and the closure our imaginations make in the gutters between.

Welcome to the Spectrum Age.